In the police states of “actually existing socialism,” security agencies infamously kept files on everyone, cradle to grave. Blackmail and banal corruption were systematically insinuated into everyday life by the state, in order to produce informers – compromised, pliable individuals caught in webs of dependency, suspicion and impotence. A particular form of prohibitive control: a specific social relation and its corresponding subjectivity.

In contemporary capitalism (Todd McGowan, Yannis Stavrakakis and others propose), such old-school prohibition societies have been transformed into societies of “commanded enjoyment.” Enjoy! is the new directive. Discover and express yourself, by freely spending your money! No money? No problem, buy on credit! This command seems to reverse the basic bourgeois values of personal self-discipline, of saving and delayed satisfaction, of not spending what you don't have.

But in fact, even in economies of relaxed credit, the imperatives of lifelong commodity consumption – of the restless exploration of identity through the purchase of products and the auratic fantasies that surround them – demand the internalization of work discipline and all the integrations it implies. Overall, avid consumers have to

work longer to earn more, and the crisis that reasserts this rule only proves it. (Think Greece, right now.)

Accommodation and resignation are thus the price of interpellation into the commodity world. To enjoy what feels like freedom, we structure obligatory social constraints on the inside of our subjectivity, as the new forms of dependency, discipline and limit. It works, because our commodity fantasies do deliver a partial enjoyment that keeps us seeking and buying, and therefore accommodated. The given doesn’t give all it promises, but it apparently gives more than anything else on offer.

Yes,

enjoyment seems to be one key to our social reality. But, as this singer of scurvy tunes keeps insisting,

enforcement is its necessary shadow: state terror takes new forms today. Moreover, these forms are vastly more powerful than the crude forms of old.

Online social networking suffices to make the point. Through the games of self-display played on Facebook and blogs (this one not excluded), we compile archives that are probably more revealing than the

Stasi files of the East German police state. We enthusiastically publish our desires and fantasies, in words and images that always say more than we intend.

We hardly think about this organized indiscretion, this voluntary abandonment of inhibitions, which we moreover perform for free. But in fact, our habitual self-exhibitions and our interactions with other self-exhibitors silently accumulate in digital form, on distant servers we are hardly aware of.

There, they merge with the other accumulated traces of our movements and purchases, now become objects of data miners and hackers, actual and potential. In the first instance, of course, we are induced to profile ourselves for the attentions of marketers. But the state – and let’s not forget that the Internet originated as a project of the US Department of Defense – has access to all of it, as the “war on terror” has taught us.

So, yes, enjoy! And in so doing, archive your history, memory, and fantasy life. It’s fun! This is the carrot of late capitalist governmentality and industrialized virtual culture, and Lacan and Foucault, as well as Adorno, can help us to grasp it.

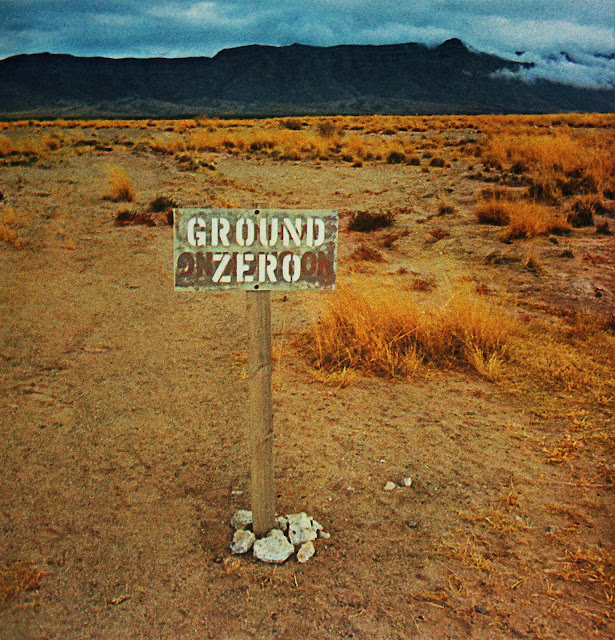

But don’t forget the stick! Powers of terror and enforcement have not withdrawn from the scene – they have expanded in unprecedented and qualitative ways. In the nuclear global regime of national security-surveillance states, techno-power overwhelms politics and ethics through the fatal knotting of war machine, science and state.

For enjoyment and enforcement go together. Integration and administration are increasingly internalized into the forms and structures of contemporary subjectivity: by enjoying in the approved ways, we largely police ourselves.

But no system attains the totalization it aims for. At all the points where the repressed returns, where the real exposes the failure of systematic enjoyment to deliver what it promises, rebellious subjectivities and uprisings incessantly break out.

We’ve already imagined, in film and fiction, where these developments tend: our self-compiled archives will be linked to terminator robotics. Nano killer-drones will be dispatched to eliminate subjects in revolt – eventually, for this is the immanent logic of exceptional security, preemptively.

If we know this, and keep mouse-clicking anyway, is this form of disavowal an aspect of our enjoyment? Probably. The forms of our sociability expose us, and silence doesn’t get us out of this circle.

Enforcement, at bottom, is necessary because the current system of enjoyment is antagonistic in specific and unsustainable ways: socially and ecologically, the limits of capital accumulation loom.

The radical response, faithful to “what is still now and then called humanity,” is to

politicize these erotics.