A nine-panel comic by Michael Baers.

Saturday, August 28, 2010

Friday, August 20, 2010

manifesto of the 130

Open Letter to French President Nicolas Sarkozy

16 August 2001

published in Libération

The French government has indicated that it is pursuing possible legal action against the Committee for the Reimbursement of the Indemnity Money Extorted from Haiti (CRIME) over a Yes Men-inspired announcement last Bastille Day pledging that France would pay Haiti restitution.

We believe the ideals of equality, fraternity and liberty would be far better served if, instead of pouring public resources into the prosecution of these pranksters, France were to start paying Haiti back for the 90 million gold francs that were extorted following Haitian independence.

This “independence debt,” which is today valued at well over the 17 billion euros pledged in the fake announcement last July 14, illegitimately forced a people who had won their independence in a successful slave revolt, to pay again for their freedom. Imposed under threat of military invasion and the restoration of slavery by French King Charles X, to compensate former colonial slave-owners for lost “property” (including the slaves who had won their freedom and independence when they defeated Napoleon’s armies), this indemnity burdened generations of Haitians with an illegitimate debt, which they were still paying right up until 1947.

France is not the only country that owes a debt to Haiti. After 1947, Haiti incurred debt to commercial banks and international financial institutions under the Duvalier dictatorships, who stole billions from the public treasury. The basic needs and development aspirations of generations of Haitians were sacrificed to pay back these debts. Granting Haiti the status of Highly Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) and canceling part of the current debt only begins to reverse the financial damage done by these recent debts. More recently, in 2000, Inter-American Development Bank loans of $150 million for basic infrastructure were illegally blocked by the US government as a means of political pressure. This also did measurable economic and human damage. Each of these institutions and governments should be responsible for the harm they did to Haiti's society and economy.

In 2003, when the Haitian government demanded repayment of the money France had extorted from Haiti, the French government responded by helping to overthrow that government. Today, the French government responds to the same demand by CRIME by threatening legal action. These are inappropriate responses to a demand that is morally, economically, and legally unassailable. In light of the urgent financial need in the country in the wake of the devastating earthquake of January 12, 2010, we urge you to pay Haiti, the world’s first black republic, the restitution it is due.

Tariq Ali, Gilbert Achcar, Michael Albert, Pierre Alferi, Jean-Claude Amara, Kevin B Anderson, Roger Annis, Anthony Arnove, Alain Badiou, Étienne Balibar, Nnimmo Bassey, Rosalyn Baxandall, Pierre Beaudet, Dan Beeton, Walden Bello,Medea Benjamin, Andy Bichlbaum & Mike Bonnano, Serge Bouchereau, Myriam Bourgy, Houria Bouteldja, José Bové, Leslie Cagan, Aldrin Calixte, Ellen Cantarow, Camille Chalmers, Noam Chomsky, Stefan Christoff, Jeff Cohen, Jim Cohen, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, Brian Concannon, Raphaël Confiant, Mike Davis, Warren Davis, Nick Dearden, Rokhaya Diallo, Christine Delphy, Rea Dol, Ariel Dorfman, Stephen Duncombe, Berthony Dupont, Ben Ehrenreich, Joe Emersberger, Yves Engler, Eric Fassin, Dianne Feeley, John Feffer, Anthony Fenton, Bill Fletcher, Jr., Eduardo Galeano, Grazia Ietto-Gillies, Greg Grandin, Arun Gupta, Peter Hallward, Hamé, Hammond, Thomas Harrison, Helene Hazera, John Hilary, HK, Doug Ireland, Kim Ives, Olatunde Johnson, Eva Joly, Mario Joseph, Mathieu Kassovitz, Robin D. G. Kelley, Richard Kim, Amir Khadir, Sadri Khiari, Naomi Klein, Pierre Labossiere, Joanne Landy, Fanfan Latour, Charles Laurence, Jesse Lemisch, Reed Lindsay, Pauline Londeix, Isabel Macdonald, Christian Mahieux, Henri Maler,Noël Mamère, Betty Reid Mandell, Marvin Mandell, Jerome Martin, John G. Mason, Gustave Massiah, Georgina Murray, Cyril Mychalejko, Robert Naiman, Jan Nederveen Pieterse, Bernard Noël, Derrick O'Keefe, Karen Orenstein, Rosalind Petchesky, Wadner Pierre, Kevin Pina, Justin Podur, Serge Quadruppani, Adam Ramsay, Jacques Rancière, Judy Rebick, William I. Robinson, Pierre Rousset, Stephen R. Shalom, Bobbi Siegelbaum, Steve Siegelbaum, Fanny Simon, Eyal Sivan, Ashley Smith, Jeb Sprague, Louis-Georges Tin, Cornel West, Howard Winant, Cécile Winter, Lawrence Wittner, Marie Yared, Nick Nesbitt, Melanie Newton

Thursday, August 12, 2010

after the occupation

Middlesex, the Morning After

by "Joe Jack-Toe"

Since my post to Scurvy Tunes back in May (“The Struggle at Middlesex,” 14 May 2010), much has happened in the conflict between staff/students and management over closure of philosophy programmes at Middlesex University, and all in all the outcome has not been good.

The students occupying University buildings were served a writ and evicted. Further protests and occupations met with heavy-handed opposition from the management, who suspended staff and students for their involvement, and launched what was essentially a smear campaign claiming that the students had “broken bones” of a member of security staff during the occupation (something patently untrue). Several staff who sent public emails criticising management through the University email system were disciplined. On 28th May, the (sluggish) lecturer’s union (UCU) finally got involved, issuing an ultimatum to management to lift the staff suspensions or go into formal dispute. On 2nd June this dispute was declared, but on 8th June the Centre for Research in Modern European Philosophy announced that it had done a deal to move to Kingston University on the other side of London, effectively robbing the campaign to save philosophy at Middlesex of its gathering momentum.

To call this rescue of the centre a merely a “partial victory” (as CRMEP’s statement did) is rather an understatement of just how slim the achievement was. The good news about the outcome was that CRMEP, and its excellent and valuable work in the study of traditions of European and radical thought can continue, and this is, in the end, something to cheer for.

However, the form in which it has been saved is a much reduced one: only postgraduate teaching and research and no undergraduate programmes will move to Kingston; furthermore, two members of staff from the department have not been included in the deal, and now face an uncertain future of redundancy or redeployment. Had the management at Middlesex proposed such an outcome (job losses and axing of programmes) the reaction would have been indignation. In effect CRMEP have acceded willingly to a programme of “rationalisation” and downsizing of the sort that we should be vigorously resisting as damaging to the nature of education and to the rights of people to receive an education (and not just job training). Moreover, once the current BA students have finished their courses, there will be no philosophy at Middlesex University: the very thing which we fought against has now come about.

What the staff at CRMEP have done is understandable and the inevitable result of a rationality which is forced on them – both in terms of their individual careers, and (to view the matter a little more generously) in terms of their commitment to the continuation of a key institution in the dissemination of radical continental thought within Anglophone academic discourse. However, for the undergraduate students, and for other staff in the humanities at Middlesex it feels like something of a betrayal (especially to the undergraduate students who have placed their futures on the line by protesting, and the academic staff who have been picked out to be disciplined for their open criticism of management).

The students’ brilliant campaign – largely using “web 2.0” technologies – to save the department caused a storm of controversy, with a petition drawing over 18,500 signatures and a Facebook site with over 14,000 members. On the back of this, the international outcry of academic superstars raised coverage not only in the blogosphere but the national press. Shortly before the CRMEP announcement the management were beginning to look profoundly discomforted by all this negative publicity and cracks between the positions of different senior staff seemed to be opening up. (As Bruce Lee says in Enter the Dragon: “The enemy has only images and illusions… Destroy the image and you will break the enemy.” Debord could hardly have put it differently.)

The success of this campaign, and the prestige of the Philosophy department offered a rallying point to those of us worried about the wider general tendencies within the University (and HE more generally) of which this was so obviously symptomatic - tendencies to cut humanities subjects, to yoke education to the vocational, to transform it from a right into a commodity and to subject it to calculations of profit so narrow as to make them almost arbitrary. The highly visible campaign was a battle within a larger struggle within the University, and CRMEP’s retreat to Kingston leaves those in other vulnerable (and less prestigious) areas feeling as if the rug on which their opposition was able to stand has been pulled out from beneath their feet. When smaller, less “important” departments are picked off in future, it will be much harder to mount a campaign against such cuts than in this case.

What also emerged clearly into the light of day in the controversies around philosophy were the highly irregular and arbitrary ways in which power is exercised in Middlesex: the general lack of accountability or safeguard procedures within the University and also the ability of management to ride roughshod over what few safety checks and balances there are. The decisions made over philosophy opened an opportunity to challenge these systems and procedures to which all of us are subject. The flight of the department means they will now be hard to challenge.

This lack of accountability may be a contributory factor as to why the protests at Middlesex have been so much less successful than in other recent cases in other Universities. (In older Universities, decisions to close down courses may need to go through an academic Senate, for example. A look through the biographies of the Board of Governors at Middlesex is also informative: they are all heavily invested in the marketisation of education.)

The management had other advantages at Middlesex. As a multi-campus University, the staff at Middlesex are more than usually dispersed and isolated. Divide and conquer has long been the order of the day: other departments that have been closed in the recent past have gone with hardly a splash in the consciousness of others, who are looking only after their own patch. Management at Middlesex, furthermore, have a stranglehold over the use of the University’s email systems so that only “official” emails can be sent globally to all staff. Many thus knew nothing, little, or only what management told them about the dispute. Perhaps the management at Middlesex were also just smart in the choice of when to announce the closure: at the end of a term, when staff were finishing teaching, and preparing to disappear to pursue the research projects which have increasingly been squeezed into Summer months by increasing teaching loads. This made organization (and industrial action) difficult.

The background of a lack of solidarity was exacerbated by the weakness of the Union. In spite of strong feelings from the membership, UCU officials seemed loathe to get involved in the dispute – partly, I think, because they are invested in a system of everyday local bargaining over small issues, and were slow to recognise this as a matter of a crisis rather than business as usual. Arthur Husk, the Branch Chair, talked of avoiding an “equal and opposite” reaction from the University administration, and voiced a belief that management was ready to negotiate as soon as they could without loosing face. This placatory attitude meant that Union involvement was slow to come. Perhaps if it had come sooner, it would have forced the matter to some kind of resolution before the move to Kingston was announced. Union caution is, however, understandable, with the general weakness of Unions under current legislation in the UK. In a recent ruling on a dispute in the HE sector, for example, a precedent was set upholding the right of employers to withhold all pay for even the smallest withdrawal of labour, as with “industrial action short of a strike.” The Student Union was even less involved. But then, when the SU proclaimed support of a sit-in on the art and design campus back in 1989, they were held liable for damages and were still paying the University back many years later.

All in all, this has been something of a gloomy picture I have painted. But are there grounds for hope too? What positive lessons can be learned from the Middlesex philosophy fiasco? First, off, of course, one of the achievements of the campaign is the rescue of CRMEP - perhaps without the strong campaign, this could not have been achieved, or would have been achieved on even less favourable terms.

Second, the creativity and energy of the students’ campaign is also to be praised, and stands as a positive model. Their technologically savvy but also grassroots strategies (drawing on the legacy of 1968 and the anti-globalization movements) were highly effective in drawing support and publicity, hitting the University in its most sensitive area, which is to say: its public image. During occupation, University buildings were transformed into temporary autonomous zones of creation, critique and festival: they were, that is to say, exactly what a University should always be…

Finally, even if Middlesex faces the inevitability of further rounds of cuts, and now without a philosophy department, so with an altogether less lively academic culture for that, I hope that what the campaign has brought about is an increased awareness amongst staff and students in the University of the threat hanging over them, of the need to take collective action (rather than minding their own patch), and of the possibilities of campaign. It was Rosa Luxemburg who saw the revolutionary defeats of the present and the past as preparing the ground for a future victory. I can only hope that the experience of increased solidarity which gathered around the Save Middlesex Philosophy Campaign, and the network of contacts with campaigners in similar situations in other Universities will remain resources in the coming months.

And in any case, is the campaign really over? Talking to some of its campaigners, they told me that they had suspended the campaign over Summer, but were looking to begin it once more when term starts again, with the aim of re-establishing a philosophy course at Middlesex, and with the aim of challenging the processes through which the courses were closed. Save Middlesex Philosophy may grow into a “Save Middlesex” campaign per se, just one cog in a larger machine of protest against the current policies of the marketisation of education and everything that this entails.

Labels:

joe jack-toe,

signals,

struggles

Friday, August 6, 2010

against forgetting

"Articulating the past historically does not mean recognizing it 'the way it really was.' It means appropriating a memory as it flashes up in a moment of danger. Historical materialism wishes to hold fast to that image of the past which unexpectedly appears to the historical subject in a moment of danger. The danger threatens both the content of the tradition and those who inherit it. For both, it is one and the same thing: the danger of becoming a tool of the ruling classes. Every age must strive anew to wrest tradition away from the conformism that is working to overpower it. The Messiah comes not only as the redeemer; he comes as the victor over the Antichrist. The only historian capable of fanning the spark of hope in the past is the one who is firmly convinced that even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he is victorious. And this enemy has never ceased to be victorious."

Walter Benjamin, "On the Concept of History" (1940), thesis VI.

It's a struggle - to remember the victims, to mourn and ask again what is to be done. To denounce the criminals and their crimes, refuse the unceasing invitations to their victory celebrations, their false reconciliations and commanded identities.

Genocidal techno-power is no accident. It is an appearance-form of a master logic: the unfolding of a global social process, capitalist modernity and its proliferating antagonisms, the sequential crystallizations of the social force field, its relations and tendencies.

The moments and turns of class struggle on a global scale, the hot house of racing accumulation and imperialist rivalry, the emergency mutations of the capitalist state, administration and integration, the use and normalization of terror - in a word, enforcement.

Now, this year, the spectacle announces, "the world" will commemorate Hiroshima Day. And for the first time, an official US envoy will "attend" ceremonies in the city destroyed by the first use of nuclear WMDs on this day 65 years ago.

What is the meaning of this "envoy" and this "attendance"? Does it announce that the perpetrating state will now express some form of official regret or apology? No. And what if it did? The only statement that would not be another dissembling victory of conformism would be a the speech of serious acts and measures toward disarmament and nuclear abolition.

Instead, the official rhetoric in this direction is covering a massive increase in US spending on the nuclear arsenals: 'modernization' processes that will lock in these WMDs and the US state's continuing dependence on them for another half-century.

The struggle against forgetting is waged from the bottom up. It has nothing to do with the official commemoration of states or the pseudo-critical mouthing of national stains. The work of this struggle is ours to do, with hell hounds at our heels.

GR

GR

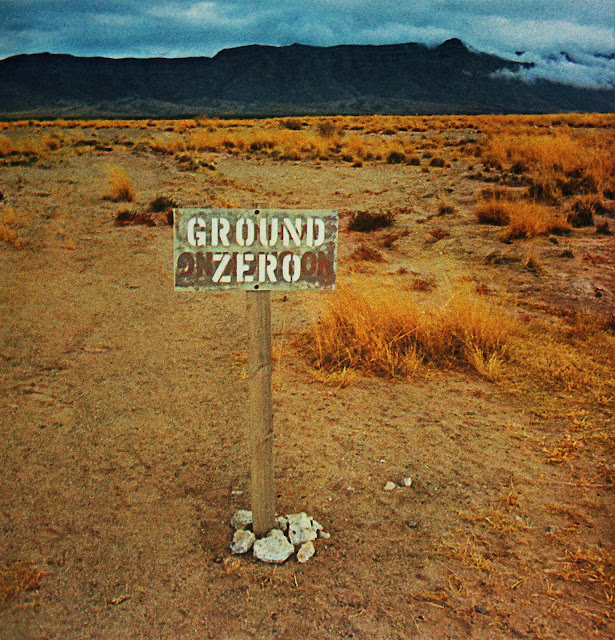

day of infamy

Guerrilla street theater by the Carnival of Democracy Players, Sarasota, Florida, 6 August 2001.

Photos by Gaby.

Wednesday, August 4, 2010

manifesto of the 121

Declaration on the Right to Insubordination in the War in Algeria

(5 September 1960)

A very important movement is developing in France, and it’s necessary that French and international opinion be better informed about it at a moment when a new phase in the War in Algeria must lead us to see, and not to forget, the depth of the crisis that began six years ago.

In ever greater numbers, French men and women are pursued, imprisoned, and sentenced for having refused to participate in this war, or for having come to the assistance of the Algerian fighters. Distorted by their adversaries, but also softened by those who have the obligation to defend them, their reasons, for the most part, are not understood. Nevertheless, it isn’t enough to say that this resistance to public authority is respectable. As a protest by men wounded in their very honor and in the idea they have of the truth, it has a meaning that goes far beyond the circumstances in which it is affirmed, and which it is important to grasp, however the events turn out.

For the Algerians the struggle, carried out either by military or diplomatic means, is not in the least ambiguous. It is a war of national independence. But what is its nature for the French? It’s not a foreign war. The territory of France has never been threatened. But there’s even more; it is carried out against men who do not consider themselves French, and who fight to cease being so. It isn’t enough to say that this is a war of conquest, an imperialist war, accompanied by an added amount of racism. There is something of this in every war, and the ambiguous nature of it remains.

In fact, in taking a decision that was in itself a fundamental abuse, the State in the first place mobilized entire classes of citizens with the sole goal of accomplishing what it called a police action against an oppressed population, one which had never revolted except due to a concern for its basic dignity, since it demands that it at last be recognized as an independent community.

Neither a war of conquest nor a war of “national defense,” nor a civil war, the war in Algeria has little by little become an autonomous action on the part of the army and a caste which refuse to submit in the face of an uprising which even the civil power, aware of the general collapse of colonial empires, seems ready to accept.

Today, it is principally through the will of the army that this criminal and absurd combat is maintained; and this army, by the important political role that many of its higher representatives have it play — at times acting openly and violently outside any form of legality, betraying the ends confided in it by the nation — compromises and risks perverting the nation itself by forcing the citizens under its orders to become the accomplices of a seditious and degrading action. Must we be reminded that fifteen years after the destruction of the Hitlerite order, French militarism has managed to bring back torture and restore it as an institution in Europe.

It is under these conditions that many French men and women have come to put in doubt the meaning of traditional values and obligations. What is civic responsibility if, in certain conditions, it becomes shameful submission? Are there not cases where refusal is a sacred obligation, where “treason” means the courageous respect for the truth? And when, by the will of those who use it as an instrument of racist or ideological domination, the army shows itself to be in open or latent revolt against democratic institutions, does not revolt against the army take on a new meaning?

This moral dilemma has been posed since the beginning of the war. With the war prolonging itself, it is only normal that with greater frequency these moral choices are concretely made in the form of increasingly numerous acts of insubordination and desertion, as well as those of protection and assistance to Algerian fighters. Free movements have developed on the margins of all the official parties, without their assistance and, finally, despite their disavowal. Outside of pre-established frameworks and orders, by a spontaneous act of conscience, once again a resistance is born; seeking and inventing forms of action and means of struggle in a new situation where, either by inertia or doctrinal timidity, either due to nationalist or moral prejudices, political groups and journals of opinion agree not to recognize the true sense and requirements.

The undersigned, considering that each of us must take a stand concerning acts which it is from here on in impossible to present as isolated news stories; considering that whatever their location and whatever their means, they have the obligation to intervene; not in order to give advice to men who have to make their own decision before such serious problems, but to ask of those who judge them to not let themselves be caught up in the ambiguity of words and values, declare:

We respect and judge justified the refusal to take up arms against the Algerian people.

We respect and judge justified the conduct of those French men and women who consider it their obligation to give aid and protection to the Algerians, oppressed in the name of the French people.

The cause of the Algerian people, which contributes decisively to the ruin of the colonial system, is the cause of all free men and women.

Arthur Adamov, Robert Antelme, Georges Auclair, Jean Baby, Hélène Balfet, Marc Barbut, Robert Barrat, Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Louis Bedouin, Marc Beigbeder, Robert Benayoun, Maurice Blanchot, Roger Blin, Arsène Bonnefous-Murat, Geneviève Bonnefoi, Raymond Borde, Jean-Louis Bory, Jacques-Laurent Bost, Pierre Boulez, Vincent Bounoure, André Breton, Guy Cabanel, Georges Condominas, Alain Cuny, Dr Jean Dalsace, Jean Czarnecki, Adrien Dax, Hubert Damisch, Bernard Dort, Jean Douassot, Simone Dreyfus, Marguerite Duras, Yves Ellouet, Dominique Eluard, Charles Estienne, Louis-René des Forêts, Dr Théodore Fraenkel, André Frénaud, Jacques Gernet, Louis Gernet, Edouard Glissant, Anne Guérin, Daniel Guérin, Jacques Howlett, Edouard Jaguer, Pierre Jaouen, Gérard Jarlot, Robert Jaulin, Alain Joubert, Henri Krea, Robert Lagarde, Monique Lange, Claude Lanzmann, Robert Lapoujade, Henri Lefebvre, Gérard Legrand, Michel Leiris, Paul Lévy, Jérôme Lindon, Eric Losfeld, Robert Louzon, Olivier de Magny, Florence Malraux, André Mandouze, Maud Mannoni, Jean Martin, Renée Marcel-Martinet, Jean-Daniel Martinet, Andrée Marty-Capgras, Dionys Mascolo, François Maspero, André Masson, Pierre de Massot, Jean-Jacques Mayoux, Jehan Mayoux, Théodore Monod, Marie Moscovici, Georges Mounin, Maurice Nadeau, Georges Navel, Claude Ollier, Hélène Parmelin, José Pierre, Marcel Péju, André Pieyre de Mandiargues, Edouard Pignon, Bernard Pingaud, Maurice Pons, J.-B. Pontalis, Jean Pouillon, Denise René, Alain Resnais, Jean-François Revel, Paul Revel, Alain Robbe-Grillet, Christiane Rochefort, Jacques-Francis Rolland, Alfred Rosner, Gilbert Rouget, Claude Roy, Marc Saint-Saëns, Nathalie Sarraute, Jean-Paul Sartre, Renée Saurel, Claude Sautet, Jean Schuster, Robert Scipion, Louis Seguin, Geneviève Serreau, Simone Signoret, Jean-Claude Silbermann, Claude Simon, René de Solier, D. de la Souchère, Jean Thiercelin, Dr René Tzanck, Vercors, Jean-Pierre Vernant, Pierre Vidal-Naquet, J.-P. Vielfaure, Claude Viseux, Ylipe, René Zazzo.

Translation by Mitch Abidor for marxists.org, with the following introductory note:

By the fall of 1960 the war in Algeria had been going on for six years. Despite defeats, massacres and torture, the FLN was gaining in strength, and opposition in France was growing. The relative timidity of the official left, in particular the French Communist Party (PCF), which insisted on mass actions calling for peace, was offset by circles of independent leftists who actively supported the FLN. Led by one of Sartre’s lieutenants, Francis Jeanson, and the communist without a party, Henri Curiel, the porteurs de valise (valise carriers) ferried arms, men, money and papers for the Algerians. Called the Jeanson Network, the heart of the group had been arrested and was to go on trial on September 6, 1960.

The day before, the text of what was to come to be known as the Manifesto of the 121 (after the number of original signatories) was released. But it was a document more read about than read since – of the journals in which it was to appear, one was seized, and the other, Sartre’s Les Temps Modernes, came out with two blank pages in its place, the result of government censorship. The government didn’t stop at censorship. As a result of the manifesto, they put in place stiff penalties for those calling for insubordination; jobs were lost and careers temporarily shut down.

The text was originally the work of Maurice Blanchot, and was revised by several others, including Claude Lanzmann. Though more than 121 were to sign the manifesto, the publisher Jerome Lindon decided to officially stop at that number because: “it sounds nice.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)