The Tower

by Kostis Stafylakis

by Kostis Stafylakis

“The Differences between the Parts are the Subject of the Composition.”

The first years after 1974, a key period for Vangelis Vlahos’ research, saw a great boost in the production of historical literature/testimonies. As Nikolas Sevastakis points out, it was the issue of seeing justice done for the crimes committed by the colonels’ regime and for recent events in Cyprus that fueled such production, in a general spirit that called for the moral vindication of the victims and the punishment of the perpetrators. If, in previous projects, Vlahos’ main intention has been to provide the necessary material for the construction of an anti-narrative, or an alternative version of Greece’s recent political history, then the Piraeus Tower project makes such an "elliptic" use of the historical document as to allow for the emergence of a space that is open to a host of associative processes. In the lines that follow, we will attempt to navigate this enigmatic space of association.

What could be the link between this decaying, half-finished tower of Piraeus, whose construction was a project undertaken by the colonels’ regime, and Andreas Papandreou’s foreign policy in the Middle East? At first glance, the two appear wholly unconnected! It is as if the work were suggesting something to which we have no access; something we cannot possibly grasp for lack of the necessary cognitive tools that might facilitate our understanding of it. Still, what we are confronted with belongs to the recent past – the very recent past, to be more precise! Today’s eighteen-year-olds may have no picture of the state of "hyper-politicization" that was typical of the 80s in Greece; they may not be familiar with the trials and tribulations of Greek foreign policy and its inexorable dependence upon crises fitfully breaking out in the interior, upon reversals and swings shaking the country from within. And yet, no matter how apolitical a younger generation may be – now between 25 and 35 years of age – it may very well recall some of the slogans chanted during the 1981 election. Young Greeks have surely heard, even as a distant echo, slogans such as "Out of the EEC" or "Out of NATO," although none of these "threats"’ ever materialized. Perhaps they may even be carrying, stored in their memory, images of Papandreou’s meetings with leaders of the so-called "independent world" of "anti-imperialist powers." If anything, they are certainly aware of Greece’s excellent relations with the Arab world, although they may be less familiar with such political choices as a verbal support of the Jaruzelski regime, a close relationship shared with the PLO and declarations made in favour of the Sandinistas –choices stemming from a determination to make perfectly clear that "Greece should no longer be considered a submissive satellite of the West." They may well remember the era’s dominant anti-Western and anti-American rhetoric, which was nevertheless accompanied by a full renewal of the contract allowing US military bases on Greek soil. They may have heard something about the strategy of greeting EEC and NATO communiqués with endless memoranda, as about the steady course steered by the Papandreou administration in constantly adopting a different position to that stated in such communiqués. They may even have heard that this strategy went hand in hand with a warm welcome of development funds provided for by the EEC’s Integrated Mediterranean Programs.

What then happens when one is confronted with Vlahos’ stark, indexical space? What would a younger viewer surmise from a first, hasty attempt at "reclaiming" historical time? They would probably form the impression that Piraeus’ emblematic commercial tower, a token of an economic policy that directly depended upon the geopolitical realities of the Cold War, is a symbol of the past that remains unconnected to the sort of "independent," "heroic" foreign policy pursued in the years of the metapolitefsi [“regime change,” referring to the return to democracy following the Junta]. The historical circumstance that established Andreas Papandreou as a leading figure on the international diplomatic chessboard, the notorious "Elounda Bay Agreement" (1984), is mysteriously cited alongside the architectural models of the Piraeus Tower. A series of photographs showing Papandreou, Qaddafi and Mitterrand, taken at this event from different angles and by different photographers, serve to remind us of Papandreou’s initiative for Greek mediation in the conflict between France and Libya, which ultimately led to a compromise between the warring parties the two countries supported in Chad. On a first level then, an associative processing of the information at hand might allow us to identify a gap, a discontinuity that supposedly symbolizes the transition from a period of oppression in Greek history to one of "freedom," of popular sovereignty and socialist political choices. As a matter of fact, a large portion of what is known today as the "socialist or democratic wing" continues to view that "heroic" period of Greek socialism with intense feelings of nostalgia, perhaps as a reaction to the "discontent" and "embarrassment" caused in them – for reasons open to discussion – by the period of "modernization."

What then happens when one is confronted with Vlahos’ stark, indexical space? What would a younger viewer surmise from a first, hasty attempt at "reclaiming" historical time? They would probably form the impression that Piraeus’ emblematic commercial tower, a token of an economic policy that directly depended upon the geopolitical realities of the Cold War, is a symbol of the past that remains unconnected to the sort of "independent," "heroic" foreign policy pursued in the years of the metapolitefsi [“regime change,” referring to the return to democracy following the Junta]. The historical circumstance that established Andreas Papandreou as a leading figure on the international diplomatic chessboard, the notorious "Elounda Bay Agreement" (1984), is mysteriously cited alongside the architectural models of the Piraeus Tower. A series of photographs showing Papandreou, Qaddafi and Mitterrand, taken at this event from different angles and by different photographers, serve to remind us of Papandreou’s initiative for Greek mediation in the conflict between France and Libya, which ultimately led to a compromise between the warring parties the two countries supported in Chad. On a first level then, an associative processing of the information at hand might allow us to identify a gap, a discontinuity that supposedly symbolizes the transition from a period of oppression in Greek history to one of "freedom," of popular sovereignty and socialist political choices. As a matter of fact, a large portion of what is known today as the "socialist or democratic wing" continues to view that "heroic" period of Greek socialism with intense feelings of nostalgia, perhaps as a reaction to the "discontent" and "embarrassment" caused in them – for reasons open to discussion – by the period of "modernization."

I think this might help us draw certain useful political insights. It is helpful to understand that the identity of contemporary Greek political awareness is still largely determined by a stereotypical "before-and-after" type of division. Thus, the documentational space that Vangelis Vlahos creates by juxtaposing photographic documents and architectural models operates as a sort of psychological experiment, or a general knowledge board game like the ones we used to play when little. The document reveals nothing about history; it rather reveals something about subjects themselves, who project their own fragmentary narrative upon the historical trace, attempting to ensure their ideological integrity by means of identifying a clear distinction between a "before" and an "after."

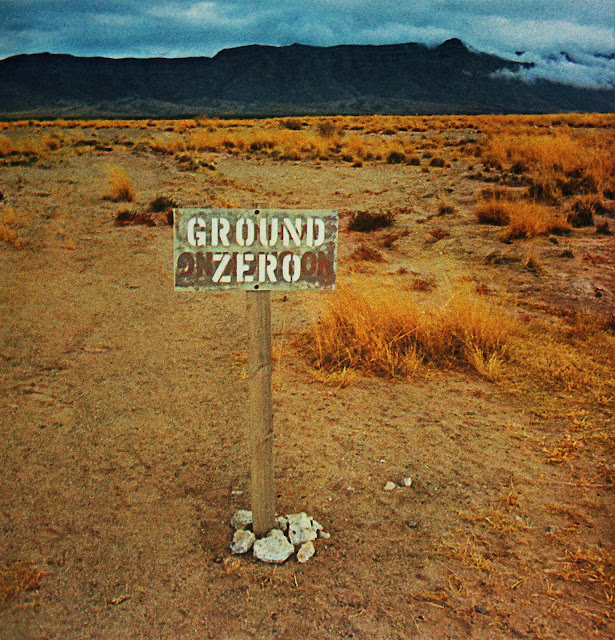

And yet, things are not that simple. Those on the receiving end of the project feel that there is something disturbing lurking within it – something that threatens their very own ideological makeup. There is something slightly off about its image. This lifeless building of Piraeus does not rise in the middle of some ruined Balkan or Middle-Eastern ghost-city, but right at the heart of a large and thriving port of the Mediterranean. Moreover, it seems that it was always on the agenda of successive administrations of the metapolitefsi years, which was ensured mainly through the Piraeus Port Authority. Still, despite political planning, the building continues to stand in its place like a menacing apparition. For several reasons that remain largely unknown, including unsubstantiated rumors about the building’s flawed statics, it was never used, save the few stores that were occasionally housed there. How ironic! After 1974, the building’s first two floors would house a toy store, a home appliances chain store and a school. What could best describe the period’s pervasive hope for prosperity if not that? At the beginning of the 80s, part of the building’s exterior was covered with marble and glass. Nevertheless, there is some inexplicable reason that still prevents completion of the building, keeping it in this state of the modernist grid/framework that forms the core of an American architectural style now adopted internationally, which one may identify in almost all the buildings Vlahos chooses to examine in his work. Of course, the marble and glass fittings on the exterior of the Piraeus Tower seem to bring this international style closer to the sort of "Greco-international" style later to be imposed by a fledgling class of managers along Kifissias avenue. Perhaps what this citing of seemingly "incongruous" documentation really achieves is to intimate a sense of continuity – the enduring nature of the imaginary realm of political power, on which the change of regimes or administrations has no bearing. It is indeed hard to offer an explanation of the building’s mysterious "resistance" to governmental plans. In the end, the building is nothing but an empty shell, a modern carcass that remains unaltered – or, perhaps, keeps returning to the same place, if a metaphor might be allowed.

On the issue of justice for the crimes of the Junta, see, Nikolas Sevastakis, Koinotopi chora: Opseis tou dimosiou chorou kai antinomies axion sti simerini Ellada (Commonplace Land: Aspects of Public Space and Value Antinomies in Contemporary Greece), Athens, 2004. For an analysis of Greek foreign policy during the early 1980s, see Nikiforos Diamandouros, Politismikos dyismos kai politiki allagi stin Ellada tis metapolitefsis; in English as Cultural Dualism and Political Change in Post-Authoritarian Greece, translated by Dimitris A. Sotiropoulos, Athens, 2000.

No comments:

Post a Comment