Limits of Terror:

On Culture Industry, Enforcement and Revolution

by Gene Ray

Excerpt:

On Culture Industry, Enforcement and Revolution

by Gene Ray

Excerpt:

These reflections suggest that a break with the master logic of accumulation entails disarming the technocratic national security-surveillance state, and above all the US war machine that is the main enforcer of the global imperialist process. To put it more pointedly: without disarmament, the prospect of emancipating system change is nill. Possibilities for transformation would increase in pace with progressive disarmament, however, and indeed the latter would measure the former. If this is so, then struggles will be strategic only insofar as they articulate themselves with anti-militarist struggles and make their own the aim of dismantling state war machines. Disarmament implies confronting the neo-imperialist state and need not be naïvely pacifist, but obviously this confrontation cannot take the form of a suicidal war of annihilation. Total struggle, mirroring total war, is terminal: pursued without limit or reserve it becomes the terror it aims to fight. And yet effective struggles need to be grounded in everyday experience; they are robust and resilient insofar as they are lived fully and vividly, pulsing beyond a mere convenience emptied of risk. The tight-wires of practice are strung under tension across these aporias. In our world of normalized emergency, the desire to be liberated from fear and terror is the long, gently bowed balancing pole of sanity.

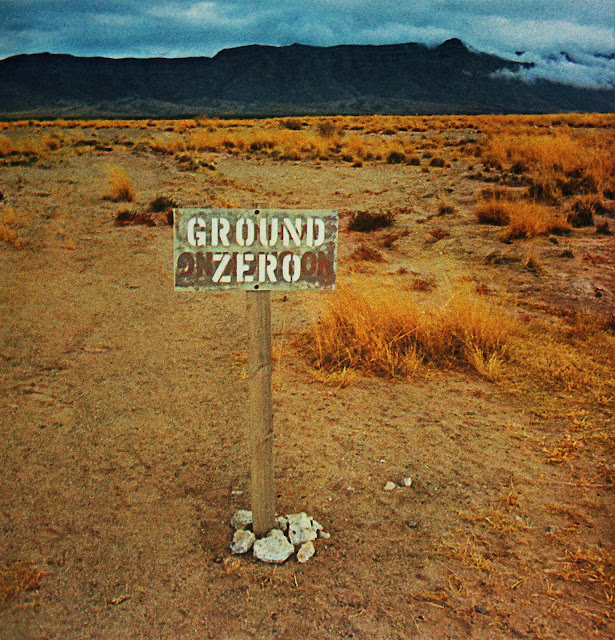

The traversing refusal of imposed fear and terror has clear aims to struggle for: the immediate cessation of all military occupations and interventions and the permanent closure of the global network of neo-imperialist military bases and spy stations that supports them; the global abolition of nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction, without exception; the radical reduction of military spending and the redirection of these funds to the urgent amelioration of social misery. Every real step toward these aims would already be radical change. And only by passing through them can struggles for autonomy, happiness and the liberation of nature have their chance to survive and grow fruitful. There is no liberation within the politics of fear: liberation as such begins and is coextensive with liberation from state terror.

The traversing refusal of imposed fear and terror has clear aims to struggle for: the immediate cessation of all military occupations and interventions and the permanent closure of the global network of neo-imperialist military bases and spy stations that supports them; the global abolition of nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction, without exception; the radical reduction of military spending and the redirection of these funds to the urgent amelioration of social misery. Every real step toward these aims would already be radical change. And only by passing through them can struggles for autonomy, happiness and the liberation of nature have their chance to survive and grow fruitful. There is no liberation within the politics of fear: liberation as such begins and is coextensive with liberation from state terror.

This essay is forthcoming in a special issue of Brumaria on Revolution and Subjectivity, out in December (The other contributors are Alain Badiou, Alex Callinicos, Simon Critchley, Barbara Epstein, John Bellamy Foster, David Harvey, John Holloway, Domenico Losurdo, Michael Löwy, Milos Petrovic, Antonio Negri, Alberto Toscano and Slavoj Žižek). The whole essay is posted here with images of the massive sit-in in Okinawa and other global struggles to close US military bases.

Limits of Terror:

On Culture Industry, Enforcement and Revolution

by Gene Ray

‘Enjoy your precarity!’ This is the command behind the bubbling ideological re-descriptions and compensating revalorizations of the so-called creative industries. If such a command is to stick, it needs appeal, allure, mystique. The figure of the artist as creative rebel, dusted off and shined up, seems to do the trick. In the new imaginaries of post-Fordist cognitive capitalism, the old categories of autonomy and creativity are jolted back to life and luster. On the subjective level, it’s all about moods, fantasies and libidinal investments. Self-exploitation can be hip, if deep knee-bends are performed to an appropriate sound track. It really is possible to find freedom in unfreedom, correct living in the false, if only you look for it in the new and approved ways. How much potential for resistance comes with these shifted productive relations and this readjusted subject of labor is a matter of some dispute.

In any case, trends in the labor market, characterized by a painful intensification of precarity, dependency and demoralization, are evidently a firmly established aspect of the contemporary social process, even if claims about post-Fordist production arguably are more applicable to certain sectors in the Global North than generalizable as capital’s new avant-garde.[*] Such shifts clearly have a material basis, not least in the dominant position capital has for decades held in the global force field. Neo-liberalism may be more than ever exposed by the current economic and biospheric meltdowns. But whatever legitimation crisis it suffers as a result, the social processes this hegemonic ideology was shaped to cover and justify are proceeding apace; with regard to policy and state interventions, this aggressive, offensive posture in the class war against labor has ceded hardly any momentum at all. In Europe in 2010, misery is advancing under the sign of an ‘austerity’ aiming to protect finance capital and mop up the remnants of organized labor-power. ‘There is no alternative’ is still the official mantra of the day, even among ‘socialist’ governments. At this writing only in Greece has there been massive popular resistance to the immiseration program; in Spain and France the unions are stirring and may yet show some fight. Mostly, though, austerity proceeds amid strikingly little contestation.

How are we to explain this remarkable intransigence of capital in its neo-liberal posture? The classical balance of forces framework offers a sobering optic. It suggests that capital can go on wreaking such havoc because labor as an organized counter-power has been decomposed and pulverized. The reasons for this de-organization are debatable. Is it due to decisive defeats and co-optations – the result of a cumulative overpowering? Or is it rather attributable to deep shifts in the organization of social production, shifts in which labor has actively participated, by its selective resistance and exodus? But even the latter appears more and more as another form of defeat today, as the real and continuing costs of labor-power’s weakness in relation to capital relentlessly come to light.

Today renewed debates over communism are flaring on the edges of academe; these at least throw into relief once again the wager and stakes of a serious and strategic anti-capitalism. The hypothetical return to communism may work as a provocation and stimulus to thought, but whether this tarnished legacy really offers a vector of leftist renewal is more dubious. The Communist Parties of the early Third International – before the self-mutilating corruptions of Stalinism and the decimating attacks of fascism – constituted a credible challenge to capitalist power. But these organizations in the event did not suffice: the world revolution had stalled by 1923, and the Parties discredited themselves to the point that, fifty years on, the exploited had abandoned them and their marginalized splinter formations in decisive exodus. The collapse of Soviet-style ‘really existing socialism’ helped to fuel a decade of neo-liberal triumphalism and encouraged gloating post histoire pronouncements about the death of revolution. The reasons for the demise of Soviet imperialism are complex and debatable, and the subsequent resurgence of Russian imperialism and the rapid rise of Chinese state capitalism do not make the task of critical interpretation any easier. What these restructurings portend in the long run for other models of socialism remains to be seen. But the defeat, over the course of the last century, of the revolutionary hopes released by the Russian Revolution at the very least puts in question the conception of revolution that took the Bolshevik vanguard as its model.

The idea of revolution, however, is not bound to this historical model and is not compromised by its defeat. The global happiness and freedom that capitalism promises but fails to deliver are negative pointers to a world beyond the misery of exploitation and domination. Such a world is utopian, if it remains unconcerned with its own conditions of possibility, if it fails to seek practical and strategic pathways by which it can be realized. The idea of revolution is first of all an emphatic insistence that freedom and happiness should be actualized and not just dreamed about. This idea entails the removal of the blockages and constraints that capitalist relations impose on human powers and potentials. These powers and potentials have been forced to develop along the channels required by the logic of accumulation. But one can easily imagine what may be possible, in terms of shared abundance and a reconciled relation to nature, if other values and social forms were not violently repressed.

On Culture Industry, Enforcement and Revolution

by Gene Ray

‘Enjoy your precarity!’ This is the command behind the bubbling ideological re-descriptions and compensating revalorizations of the so-called creative industries. If such a command is to stick, it needs appeal, allure, mystique. The figure of the artist as creative rebel, dusted off and shined up, seems to do the trick. In the new imaginaries of post-Fordist cognitive capitalism, the old categories of autonomy and creativity are jolted back to life and luster. On the subjective level, it’s all about moods, fantasies and libidinal investments. Self-exploitation can be hip, if deep knee-bends are performed to an appropriate sound track. It really is possible to find freedom in unfreedom, correct living in the false, if only you look for it in the new and approved ways. How much potential for resistance comes with these shifted productive relations and this readjusted subject of labor is a matter of some dispute.

In any case, trends in the labor market, characterized by a painful intensification of precarity, dependency and demoralization, are evidently a firmly established aspect of the contemporary social process, even if claims about post-Fordist production arguably are more applicable to certain sectors in the Global North than generalizable as capital’s new avant-garde.[*] Such shifts clearly have a material basis, not least in the dominant position capital has for decades held in the global force field. Neo-liberalism may be more than ever exposed by the current economic and biospheric meltdowns. But whatever legitimation crisis it suffers as a result, the social processes this hegemonic ideology was shaped to cover and justify are proceeding apace; with regard to policy and state interventions, this aggressive, offensive posture in the class war against labor has ceded hardly any momentum at all. In Europe in 2010, misery is advancing under the sign of an ‘austerity’ aiming to protect finance capital and mop up the remnants of organized labor-power. ‘There is no alternative’ is still the official mantra of the day, even among ‘socialist’ governments. At this writing only in Greece has there been massive popular resistance to the immiseration program; in Spain and France the unions are stirring and may yet show some fight. Mostly, though, austerity proceeds amid strikingly little contestation.

How are we to explain this remarkable intransigence of capital in its neo-liberal posture? The classical balance of forces framework offers a sobering optic. It suggests that capital can go on wreaking such havoc because labor as an organized counter-power has been decomposed and pulverized. The reasons for this de-organization are debatable. Is it due to decisive defeats and co-optations – the result of a cumulative overpowering? Or is it rather attributable to deep shifts in the organization of social production, shifts in which labor has actively participated, by its selective resistance and exodus? But even the latter appears more and more as another form of defeat today, as the real and continuing costs of labor-power’s weakness in relation to capital relentlessly come to light.

Today renewed debates over communism are flaring on the edges of academe; these at least throw into relief once again the wager and stakes of a serious and strategic anti-capitalism. The hypothetical return to communism may work as a provocation and stimulus to thought, but whether this tarnished legacy really offers a vector of leftist renewal is more dubious. The Communist Parties of the early Third International – before the self-mutilating corruptions of Stalinism and the decimating attacks of fascism – constituted a credible challenge to capitalist power. But these organizations in the event did not suffice: the world revolution had stalled by 1923, and the Parties discredited themselves to the point that, fifty years on, the exploited had abandoned them and their marginalized splinter formations in decisive exodus. The collapse of Soviet-style ‘really existing socialism’ helped to fuel a decade of neo-liberal triumphalism and encouraged gloating post histoire pronouncements about the death of revolution. The reasons for the demise of Soviet imperialism are complex and debatable, and the subsequent resurgence of Russian imperialism and the rapid rise of Chinese state capitalism do not make the task of critical interpretation any easier. What these restructurings portend in the long run for other models of socialism remains to be seen. But the defeat, over the course of the last century, of the revolutionary hopes released by the Russian Revolution at the very least puts in question the conception of revolution that took the Bolshevik vanguard as its model.

The idea of revolution, however, is not bound to this historical model and is not compromised by its defeat. The global happiness and freedom that capitalism promises but fails to deliver are negative pointers to a world beyond the misery of exploitation and domination. Such a world is utopian, if it remains unconcerned with its own conditions of possibility, if it fails to seek practical and strategic pathways by which it can be realized. The idea of revolution is first of all an emphatic insistence that freedom and happiness should be actualized and not just dreamed about. This idea entails the removal of the blockages and constraints that capitalist relations impose on human powers and potentials. These powers and potentials have been forced to develop along the channels required by the logic of accumulation. But one can easily imagine what may be possible, in terms of shared abundance and a reconciled relation to nature, if other values and social forms were not violently repressed.

No one can say for certain where necessity ends and freedom begins at any point in time: this point can only be discovered by reaching for it, by pushing collectively against the evident limits of the given. In a world in which capitalist relations and power are enforced by violence and state terror, the reach beyond the rule of antagonism has to pass through the mediations of struggle. It will not be granted as a gift from above, by the actual placeholders of power and privilege. The given structure of places, the status quo of a globally enforced social process, will have to be overthrown by struggle if it is to be abolished. The oppressed and exploited will have to liberate themselves by their own gathered power and agency, or else renounce liberation. This, I take it, remains the simple truth content of the idea of revolution, and so long as the world is capitalist it will be valid to invoke this idea.

But if, in this sense, revolution is always ‘on the agenda’, as a demand that misery makes urgent, it does not at all follow that it is just around the corner or that its necessary conditions are even minimally present. In this direction, little can be taken for granted and everything should be open to question and critical debate. Models, which preserve past approaches to problems, tend to become symbols – potent objects of reverence or hatred that absorb the intensities of the struggles they schematize. Today they should be studied carefully and even rubbed against the grain. Not as fetishes do they release their greatest use-values to the ideas of liberation and revolution; those use-values may be negative ones. What is unhappily clear today is that in the wake of the defeat of militant hope in its twentieth century forms, nothing has succeeded in recomposing the power of labor as an organized force capable of gaining and holding a position in the force field. Purged of radical aims, the approved spectacle of party politics in the capitalist democracies drifted long ago into a wasteland of unprincipled opportunism. With nothing now effectively constraining it, the ‘inspirited monster’ of accumulation runs amok – over the planet, and through our bodies and minds.

New theories that advocate abandoning the logic of the force field – theories of multitude and exodus, of anti-power and non-instrumental revolution – have wrestled admirably with the political problems we inherit but have not solved them. Those problems – of agency and organizational form, and of viable strategies and ethics of struggle – still mark the limit of emancipating social transformation. For it is not enough to organize a social form opposed to capitalist values; any alternative model or opening in normality also has to organize its effective defense against capitalist power – or will be short-lived. By this test the most influential new theories of radical transformation – Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri’s multitude and John Holloway’s anti-power – have so far been signally ineffective. Our current conjunctural predicament – antiwar movement dead in the water, movement of movements in paralysis or disarray, corporations allowed to act and states to intervene with hardly any visible resistance or contestation in the imperialist metropoles – underscores the theoretical and practical crisis. It does no good to underestimate the enemy or imagine that there is not one. A sober accounting of labor-power’s current weakness in its relation to capital and of the real and continuing costs of that weakness, in terms of increasing social misery and biospheric meltdown, would be a first condition of any strategic renewal of resistance.

Back to Benjamin and Adorno then, back to the melancholy of impasse? Old school, no doubt, but a measure of Frankfurt pessimism is bracing corrective to an optimism become foolish. It is a willful gaze that can take in the last century and still see progress. Such a return would not be unproductive in rethinking the intersections of revolution, subjectivity and culture. As many have remarked, the fashionable discourse of creative industries is premised on a neutralizing appropriation of Adorno’s critical category of ‘culture industry’. This category certainly poses the problematic of subjectivity. But it also gives heavy weight to the dominant tendencies of objective reality. It is this second aspect that is sometimes discounted in even critical responses to the celebration of creative industries. Over the course of the 1950s and 1960s, Adorno came to see ‘administration’ and ‘integration’ as the decisive immanent tendencies of late capitalism. Both, it will be shown, are inseparably bound up with the category of terror, which has to be a part of any adequate account of the global social process that dominates life today. This essay re-reads the culture industry argument against more recent approaches to subjectivation and considers the administration of terror as a gripping dialectic of enjoyment and enforcement.

The Stakes of Culture Industry

Discussions of culture industry typically begin with the famous chapter from Horkheimer and Adorno’s Dialectic of Enlightenment. There, the tendencies and processes engulfing ‘culture’ – ‘tendencies which turn cultural progress into its opposite’ – are registered across ‘philosophical fragments’ emplotting ‘the tireless self-destruction of enlightenment’: Enlightenment, the dream suicided by society. The liberation of man from a dominating ‘nature’ is converted into the class domination of man by man, and this dialectic takes catastrophic and genocidal turns under late capitalism, as the nets of the social whole tighten. The rationalized production of cultural commodities for mass consumption reinforces culture’s affirmative ideological functions in a vicious spiral. Spaces for critical autonomy tend to be squeezed out and critical capacities atrophy, leaving conformity and resignation as the paths of least resistance. In a hostile takeover and permanent occupation of leisure time, the exploitative social given advertises itself unceasingly. Mass culture, as Adorno puts it in the continuation of the chapter, becomes ‘a system of signals that signals itself’. Culture industry denotes the dominant logic of cultural ‘goods’ that are impressively varied and apparently free of direct censorship, but which nevertheless exhibit a strong tendency toward uniformity. In this they mirror the logic of the global social process, that persistence in domination that Adorno in 1951 described vividly as ‘the ever-changing production of the always-the-same’.

The culture industry chapter of Dialectic of Enlightenment was only a preliminary formulation of this thesis, however. Adorno offered some important elaborations of the argument in the 1960 essay ‘Culture and Administration’ and ‘Culture Industry Reconsidered’, from 1963. Additional glosses and remarks in passing can be found throughout his texts of the 1950s and 1960s. Moreover, the published book chapter represents only the jointly edited first half of a longer manuscript drafted by Adorno; in the 1944 mimeograph edition circulated to Frankfurt Institute members, the chapter ends with the line ‘To be continued.’ The unedited remainder was published posthumously in 1981, under the title ‘The Schema of Mass Culture’.

The additional writings do not greatly change the argument and certainly do not retract the conclusions. But the clarifications and elaborations they offer get in the way of writers wishing to dismiss those conclusions too easily, on the grounds that changes since have made them obsolete. In the new preface to the 1969 edition of Dialectic of Enlightenment, Horkheimer and Adorno acknowledge that time does not stand still; processes change as they unfold. But they insist that the tendency they pointed to continues to hold:

'We do not stand by everything we said in the book in its original form. That would be incompatible with a theory which attributes a temporal core to truth instead of contrasting truth as something invariable to the movement of history. The book was written at a time when the end of the National Socialist terror was in sight. In not a few places, however, the formulation is no longer adequate to the reality of today. All the same, even at that time we did not underestimate the implications of the transition to the administered world.'

The general tendency or immanent drift of the global process has not changed, because the capitalist logic that grounds and generates it remains in force. This general tendency is the essence of capitalist modernity, which unfolds through all the dynamic processes that are its concrete appearance-forms. It holds, so long as the social world is a capitalist one.

In ‘Culture Industry Reconsidered’, Adorno recalls that he and Horkheimer chose the term ‘culture industry’ not only to express the paradoxical merger of an at least quasi-autonomous tradition with its opposite. They also aimed to critique the concept of ‘mass culture’, with its implication of an authentically popular culture: ‘The customer is not king, as the culture industry would have us believe, not its subject but its object.’ Adorno does not hesitate to reaffirm the tendency at work. The production and consumption of commodified culture ‘more or less according to plan’ tends to produce comformist consciousness and functions in sum as ‘a system almost without gaps’: ‘This is made possible by contemporary technical capacities as well as by economic and administrative concentration.’

The term ‘industry’, then, refers to the market-oriented rationality or calculus that drives all aspects of the processes involved. It registers the fact that there is a master logic, operative through technical developments and shifts in particular processes:

'Thus, the expression ‘industry’ is not to be taken too literally. It refers to the standardization of the thing itself – such as that of the Western, familiar to every movie-goer – and to the rationalization of distribution techniques, but not strictly to the production process.'

The production processes themselves often still involve the input of individuals who have not been entirely severed from their means of production and who may be celebrated as stars – or today’s ‘creatives’. But their contributions are still integrated according to the logic of valorization and accumulation that dominates commodified culture:

'It [culture industry] is industrial more in a sociological sense, in the incorporation of industrial forms of organization even when nothing is manufactured – as in the rationalization of office work – rather than in the sense of anything really and actually produced by technological rationality.'

It is no refutation of the culture industry thesis, then, simply to point to this or that aspect of the cultural field today and note how aged and out of date those old examples from the 1940s have become. If micro-enterprises are the norm in today’s creative industries, this means little if their very existence is an effect of technology and ‘economic and administrative concentration’. The Internet feels like freedom, but Google and Verizon can still decide together how they will undo the principle of net neutrality. Nor will it suffice to point to counter-tendencies, local or not, if these do not displace the master logic; over time, generally if not in every case, the dominant tendency wins out, so long as it is dominant.

To refute the argument, it would be necessary to show that the overall drift or tendency no longer holds – or never did. The issue at stake is manipulation: the restriction, impoverishment and seduction of consciousness. Are the gaps, in which autonomous subjects can emerge and from which practices of critical resistance might produce real effects, still closing? Or are these gaps of autonomy expanding now, as some claim, indicating a reversal of the trend? How are autonomous subjects formed, anyway? What are the conditions of their formation and, if they are to be considered as ‘actors’ in a cultural field, what freedom of action is actually theirs?

Here, of course, the argument of culture industry clashes with theoretical orientations firmly established in academe in the wake of 1968. Rejecting Frankfurt pessimism, the new disciplinary hybrid of cultural studies took aim at the manipulation thesis. The dominated classes are not the passive objects of manipulation, it was countered; even as consumers, they find ways to express their resistance to control and exploitation. From one angle, scholars such as Edward Thompson, Raymond Williams and Stuart Hall insisted in Marxist terms on the existence of cultures of popular resistance, even within the forms of dominant culture. In a different vector, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, and Michel de Certeau became new reference points for an end-run around the manipulation problem that rejected the Marxist conception of social power; in this approach, the forms or modes of subjectivation constituted by specific relations of power gain priority over macro structures of exploitation and direct repression.

How far do such retorts and re-conceptions really come to grips with Adorno’s dialectic of subjectivation and the dominant objective tendency? In answering this question, we need to avoid caricatures and straw-arguments. Whatever the rhetorical hyperbole of certain formulations, Adorno does not argue that the consumers of mass culture are merely passive slaves invariably doomed to eternal reification. He is careful to acknowledge that gaps and openings for critical autonomy still exist. The argument is that the dominant process is systematically reducing such gaps and that the constriction is well advanced; those critical and autonomous subjects who do emerge are increasingly blocked from any practice that could change the dominant trend or aim radically beyond it. In this sense, the system is ‘totalizing’.

But totalizing does not and cannot mean totalized, as in actualized with an exhaustive completeness that would, once and for all, eliminate every gap and permanently block critical subjects from ever emerging again. This is a basic point of Adorno’s ‘negative dialectics’ and of his critique of Hegel. Social systems tend toward closure, but they can only actualize closure through the final solution of genocidal integrations and subsumptions; the once-and-for-all of global closure would simultaneously eliminate the conditions of the system itself, which cannot do without the subjects it needs to activate, mobilize and control. The catastrophic aspect of late capitalism is that techno-power and so-called Weapons of Mass Destruction make the literal suicide of enlightenment a real historical possibility for the first time – this is where terror will have to come in, and will do later in the essay.

The term ‘industry’, then, refers to the market-oriented rationality or calculus that drives all aspects of the processes involved. It registers the fact that there is a master logic, operative through technical developments and shifts in particular processes:

'Thus, the expression ‘industry’ is not to be taken too literally. It refers to the standardization of the thing itself – such as that of the Western, familiar to every movie-goer – and to the rationalization of distribution techniques, but not strictly to the production process.'

The production processes themselves often still involve the input of individuals who have not been entirely severed from their means of production and who may be celebrated as stars – or today’s ‘creatives’. But their contributions are still integrated according to the logic of valorization and accumulation that dominates commodified culture:

'It [culture industry] is industrial more in a sociological sense, in the incorporation of industrial forms of organization even when nothing is manufactured – as in the rationalization of office work – rather than in the sense of anything really and actually produced by technological rationality.'

It is no refutation of the culture industry thesis, then, simply to point to this or that aspect of the cultural field today and note how aged and out of date those old examples from the 1940s have become. If micro-enterprises are the norm in today’s creative industries, this means little if their very existence is an effect of technology and ‘economic and administrative concentration’. The Internet feels like freedom, but Google and Verizon can still decide together how they will undo the principle of net neutrality. Nor will it suffice to point to counter-tendencies, local or not, if these do not displace the master logic; over time, generally if not in every case, the dominant tendency wins out, so long as it is dominant.

To refute the argument, it would be necessary to show that the overall drift or tendency no longer holds – or never did. The issue at stake is manipulation: the restriction, impoverishment and seduction of consciousness. Are the gaps, in which autonomous subjects can emerge and from which practices of critical resistance might produce real effects, still closing? Or are these gaps of autonomy expanding now, as some claim, indicating a reversal of the trend? How are autonomous subjects formed, anyway? What are the conditions of their formation and, if they are to be considered as ‘actors’ in a cultural field, what freedom of action is actually theirs?

Here, of course, the argument of culture industry clashes with theoretical orientations firmly established in academe in the wake of 1968. Rejecting Frankfurt pessimism, the new disciplinary hybrid of cultural studies took aim at the manipulation thesis. The dominated classes are not the passive objects of manipulation, it was countered; even as consumers, they find ways to express their resistance to control and exploitation. From one angle, scholars such as Edward Thompson, Raymond Williams and Stuart Hall insisted in Marxist terms on the existence of cultures of popular resistance, even within the forms of dominant culture. In a different vector, Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, and Michel de Certeau became new reference points for an end-run around the manipulation problem that rejected the Marxist conception of social power; in this approach, the forms or modes of subjectivation constituted by specific relations of power gain priority over macro structures of exploitation and direct repression.

How far do such retorts and re-conceptions really come to grips with Adorno’s dialectic of subjectivation and the dominant objective tendency? In answering this question, we need to avoid caricatures and straw-arguments. Whatever the rhetorical hyperbole of certain formulations, Adorno does not argue that the consumers of mass culture are merely passive slaves invariably doomed to eternal reification. He is careful to acknowledge that gaps and openings for critical autonomy still exist. The argument is that the dominant process is systematically reducing such gaps and that the constriction is well advanced; those critical and autonomous subjects who do emerge are increasingly blocked from any practice that could change the dominant trend or aim radically beyond it. In this sense, the system is ‘totalizing’.

But totalizing does not and cannot mean totalized, as in actualized with an exhaustive completeness that would, once and for all, eliminate every gap and permanently block critical subjects from ever emerging again. This is a basic point of Adorno’s ‘negative dialectics’ and of his critique of Hegel. Social systems tend toward closure, but they can only actualize closure through the final solution of genocidal integrations and subsumptions; the once-and-for-all of global closure would simultaneously eliminate the conditions of the system itself, which cannot do without the subjects it needs to activate, mobilize and control. The catastrophic aspect of late capitalism is that techno-power and so-called Weapons of Mass Destruction make the literal suicide of enlightenment a real historical possibility for the first time – this is where terror will have to come in, and will do later in the essay.

The point about subjectivation, however, is that there are chains – there are objective constraints that function as obstacles to subjective autonomy and limit what subjects can do with their autonomy. The problem is not exhausted in the question, why do people choose their own chains (or: give their consent to the hegemonic culture). Some may do so as the result of an economic calculation, or a specific fear, or the compensatory enjoyment of more unconscious repressions. But the high stakes of the culture industry argument are in the claim that the objective tendency reaches far back into the processes by which subjects are formed. ‘Pre-formed’ subjects begin to emerge, who no longer even recognize this choice – yes or no to their chains:

'The mesh of the whole, modeled on the act of exchange, is drawn ever tighter. It leaves individual consciousness less and less room for evasion, pre-forms it more and more thoroughly, cuts it off a priori as it were from the possibility of difference, which is degraded to a nuance in the monotony of supply.'

The modes and processes of subjectivation are a proper focus, then, for the forms and qualities of subjectivity are precisely what are at stake. But these modes and processes of formation are themselves shaped and constrained in ways that cannot be avoided or dismissed: ‘Society precedes the subject.’ Subject-centered approaches are premised on the possibility of intervention into the modes of subjectivation. This entails the freedom and autonomy required to refuse an imposed or offered form of subjectivity, for example by withdrawing from a specific relation of power and domination. But how free are existing subjects? Are they masters of destiny who can do what they want, regardless of objective factors and forces? That hardly seems likely, and if they are not, then there is no reason to think Adorno has been answered or refuted.

Some post-structuralist approaches to subjectivation risk one-sidedly discounting the headlock of the objective – the constraints imposed by prevailing structures, conditions and tendencies. There is an implicit voluntarism in the assumption that subjects can simply refuse and leap out of every subjugating relation of power or de-link themselves at will from the forms of dominated subjectivity that correspond to such relations. (If they could, things would presumably be much different.) Adorno is clearly arguing against such voluntarism. But it would be a distortion of Adorno’s position to attribute to him some version of absolutized passivity and servility. For him, critical autonomy is the necessary subjective vector of emancipation. Critical subjects can still emerge, but only through the hard mental work of self-liberation – against the processes and dominant tendencies of which the culture industry is an ideological mediator. This becomes increasingly improbable as critical capacity is systematically attacked, undermined, blocked and repressed. Unlikely but still possible: Adorno also insists it cannot be excluded. Individual subjects can through their own efforts break the spell and see through the mirages of social appearance. While the conditions of autonomy objectively dwindle, its subjective condition remains the subject’s own desire for liberation.

Consider the ending of the full, extended version of the culture industry chapter:

'The neon signs that hang over our cities and outshine the natural light of the night with their own are comets presaging the natural disaster of society, its frozen death. Yet they do not come from the sky. They are controlled from the earth. It depends upon human beings themselves whether they will extinguish these lights and awake from a nightmare that only threatens to become actual as long as men believe in it.'[**]

Taken out of context, these lines could even leave an impression of idealistic voluntarism. But there is too much continual emphasis elsewhere, indeed throughout, on the objective domination of the global social process to warrant any such precipitous reading. The aporia is not that subjects cannot, here and there, break the spell, but rather that the conditions for a critical mass of such subjects, and thus for a passage to strategic social transformation, are evidently blocked.

Relative Autonomy, Resistance and Struggle

The problem with the culture industry argument is that, even if it reflects a sober and basically accurate estimation of social forces and tendencies, its pathos of pessimism threatens to become paralyzing. It tells us why there is less and less space for resistant subjects and practical resistance, without telling us what can be done about it. We are called to stand firm and seek whatever vestiges of critical autonomy are left to us, but at the same time we are told why this cannot possibly alter or transform the status quo. If critical theory does no more than reflect the given double-bind, then it too fosters resignation and contributes to the objective tendency it would like to critique. The heliotropic orientation toward praxis in late Frankfurt theory has wizened too much. The resistant subject (even qua object of exploitation and target of manipulation) cannot be less stubborn and intransigent than the agents of its systemic enemy.

One way out of the theoretical impasse opens up by pushing the notion of autonomy – not the mystified autonomy that returns in the discourses of creative industries, but the potential that is actually ours. Pure autonomy, we can agree, is a myth. For ‘autonomy’ we have to read ‘relative autonomy’. The culture industry subverts artistic autonomy and tends to absorb it, but never does so entirely. Relatively autonomous art, holding to its own criteria and to the historical logics of its own forms, goes on – and insofar as it does, it remains different from the merely calculated production of cultural commodities. Such an art shares the social guilt and is always scarred by the dominant social logics it tries to refuse. Still, by its very attempts at difference, it activates a relative autonomy and actualizes a force of resistance. In comparison, the culture industry has less relative autonomy; there capital holds sway much more directly. But even in the culture industry, there is some relative autonomy to claim and activate. Even Adorno acknowledges as much in his discussion of individual forms of production in ‘Culture Industry Reconsidered’. Although certain cultural commodities are produced through technical processes that can properly be called industrial, there is still a ‘perennial conflict between artists active in the culture industry and those who control it’.

Absolute autonomy is a sublime mirage. But so is its opposite. The absence of autonomy is slavery. But its utter absence, the elimination of even potential autonomy, would be absolute, totalized slavery – a closure impossible, short of global termination. Relative autonomy, then, is both the condition of resistance and the condition that actually obtains most of time. What varies – in the specifics of place, position and conjuncture – is the extent and kind of relative autonomy. This granted, we regain a focal point for possible practices of resistance. The culture industry, we can now see, may operate according to a dominant logic, but the operations of this logic cannot exclude all possibilities for resistance. The culture industry is not utterly monolithic, any more than the capitalist state is. It too is fissured by the tensions and antagonisms that plague any hierarchical system; it too mediates and condenses the social force-field, as a ‘crystallization’ of the forces in class struggle, as Nicos Poulantzas would have put it. To continue this analogy, the culture industry is neither an object-instrument of capital with zero autonomy nor a neutral, domination-free system in which actors can do anything, without regard for the power of capital. Obviously the institutional nexus of culture industry is also very different from the nexus of the state, but that difference can also be thought of as a difference in kind and degree of relative autonomy.

Such a focus brings back into view the class war of position and reopens the struggle for hegemony. It is compatible with the Frankfurt account, remembering the latter’s caveats about the impossibility of full systemic closure. And in re-posing the linkage of resistant practices and radical aims, it goes beyond Frankfurt pessimism, without lapsing into a naïve voluntarism or pretending that there are no grounds for worry. The project of subjective liberation is bound to the liberating transformation of the objective whole, the global process. For that aim, the unorganized league of impotent critical subjects is clearly inadequate. Even within spheres of relative autonomy, individual or cellular micro-resistance remains merely symbolic and token, if it cannot organize itself as a political force capable of gaining and holding a place in the balance. In the current weakness, the need is to recompose, reorganize and link struggles, through practical alliances and strategic fronts. Easier said than done, but concrete aims stimulate the search for strategies. Pessimism may be justified but need not freeze us: even in the culture industry, there is always something to be done.

The problem with the culture industry argument is that, even if it reflects a sober and basically accurate estimation of social forces and tendencies, its pathos of pessimism threatens to become paralyzing. It tells us why there is less and less space for resistant subjects and practical resistance, without telling us what can be done about it. We are called to stand firm and seek whatever vestiges of critical autonomy are left to us, but at the same time we are told why this cannot possibly alter or transform the status quo. If critical theory does no more than reflect the given double-bind, then it too fosters resignation and contributes to the objective tendency it would like to critique. The heliotropic orientation toward praxis in late Frankfurt theory has wizened too much. The resistant subject (even qua object of exploitation and target of manipulation) cannot be less stubborn and intransigent than the agents of its systemic enemy.

One way out of the theoretical impasse opens up by pushing the notion of autonomy – not the mystified autonomy that returns in the discourses of creative industries, but the potential that is actually ours. Pure autonomy, we can agree, is a myth. For ‘autonomy’ we have to read ‘relative autonomy’. The culture industry subverts artistic autonomy and tends to absorb it, but never does so entirely. Relatively autonomous art, holding to its own criteria and to the historical logics of its own forms, goes on – and insofar as it does, it remains different from the merely calculated production of cultural commodities. Such an art shares the social guilt and is always scarred by the dominant social logics it tries to refuse. Still, by its very attempts at difference, it activates a relative autonomy and actualizes a force of resistance. In comparison, the culture industry has less relative autonomy; there capital holds sway much more directly. But even in the culture industry, there is some relative autonomy to claim and activate. Even Adorno acknowledges as much in his discussion of individual forms of production in ‘Culture Industry Reconsidered’. Although certain cultural commodities are produced through technical processes that can properly be called industrial, there is still a ‘perennial conflict between artists active in the culture industry and those who control it’.

Absolute autonomy is a sublime mirage. But so is its opposite. The absence of autonomy is slavery. But its utter absence, the elimination of even potential autonomy, would be absolute, totalized slavery – a closure impossible, short of global termination. Relative autonomy, then, is both the condition of resistance and the condition that actually obtains most of time. What varies – in the specifics of place, position and conjuncture – is the extent and kind of relative autonomy. This granted, we regain a focal point for possible practices of resistance. The culture industry, we can now see, may operate according to a dominant logic, but the operations of this logic cannot exclude all possibilities for resistance. The culture industry is not utterly monolithic, any more than the capitalist state is. It too is fissured by the tensions and antagonisms that plague any hierarchical system; it too mediates and condenses the social force-field, as a ‘crystallization’ of the forces in class struggle, as Nicos Poulantzas would have put it. To continue this analogy, the culture industry is neither an object-instrument of capital with zero autonomy nor a neutral, domination-free system in which actors can do anything, without regard for the power of capital. Obviously the institutional nexus of culture industry is also very different from the nexus of the state, but that difference can also be thought of as a difference in kind and degree of relative autonomy.

Such a focus brings back into view the class war of position and reopens the struggle for hegemony. It is compatible with the Frankfurt account, remembering the latter’s caveats about the impossibility of full systemic closure. And in re-posing the linkage of resistant practices and radical aims, it goes beyond Frankfurt pessimism, without lapsing into a naïve voluntarism or pretending that there are no grounds for worry. The project of subjective liberation is bound to the liberating transformation of the objective whole, the global process. For that aim, the unorganized league of impotent critical subjects is clearly inadequate. Even within spheres of relative autonomy, individual or cellular micro-resistance remains merely symbolic and token, if it cannot organize itself as a political force capable of gaining and holding a place in the balance. In the current weakness, the need is to recompose, reorganize and link struggles, through practical alliances and strategic fronts. Easier said than done, but concrete aims stimulate the search for strategies. Pessimism may be justified but need not freeze us: even in the culture industry, there is always something to be done.

Terror, Culture and Administration

For Adorno, ‘integration’ and ‘administration’ named the two linked tendencies of the late capitalist global process. Integration is the logic of identity and the subsumption of particulars, and Adorno traced its workings in social facts and cultural appearance-forms, from philosophical positivism and empirical sociology to astrology columns and Walt Disney cartoons. Administration, or techno-power concentrated in specialized institutions, is congealed as the instrumental logic of entrenched and expanding bureaucracies. Social subjects are not left untouched by processes of integration and administration; in fact, these processes reach into and shape the conditions for possible forms of subjectivity. Adorno emphasizes this point in ‘Culture and Administration’:

'Administration, however, is not simply imposed upon the supposedly productive human being from without. It multiplies within the person himself. That a particular situation in time brings forth those subjects intended for it is to be taken very literally. Nor are those who produce culture secure before the "increasingly organic composition of mankind".'

The objective tendency, produced by subjects and only transformable by subjects, nevertheless constricts the forms and modes of subjectivation: this dialectic, precisely, generates the perennial catastrophe. And as already noted, these tendencies do not stop short before the physical reduction and liquidation of actual subjects. ‘Genocide is the absolute integration.’[***] Genocide, then, cannot be dismissed as a deviation from the rule of law and humanist norms, for it belongs to the immanent drift of the global process. And after the demonstrations of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, we must live in a social world in which the final integration – the global termination of systemic logic that would at the same time terminate all life and the conditions of all systems – has become objectively possible. Exit, ruined, the myth of progress.

Terror and late capitalism, then, go together. What begins as the pressure of conformity and the market – today, the terrors of precarity and the miseries of austerity – tends toward the logic of exterminism. In the last pages of ‘The Schema of Mass Culture’, Adorno elaborates the connection between the ‘anxiety, that is the ultimate lesson of the fascist era’ and techno-power in the hands of administration:

'The terror for which the people of every land are being prepared glares ever more threateningly from the rigid features of these culture-masks: in every peal of laughter we hear the menacing voice of extortion and the comic types are legible signs which represent the contorted bodies of revolutionaries. Participation in mass culture itself stands under the sign of terror.'

The conformity and resignation fostered by a system of cultural uniformity is connected, through the mediations of an unfolding master logic, to the defeats of radical struggles and the triumphs of capitalist war machines. State terror, resurgent today, declares the bogus ‘war on terror.’

For Adorno, ‘integration’ and ‘administration’ named the two linked tendencies of the late capitalist global process. Integration is the logic of identity and the subsumption of particulars, and Adorno traced its workings in social facts and cultural appearance-forms, from philosophical positivism and empirical sociology to astrology columns and Walt Disney cartoons. Administration, or techno-power concentrated in specialized institutions, is congealed as the instrumental logic of entrenched and expanding bureaucracies. Social subjects are not left untouched by processes of integration and administration; in fact, these processes reach into and shape the conditions for possible forms of subjectivity. Adorno emphasizes this point in ‘Culture and Administration’:

'Administration, however, is not simply imposed upon the supposedly productive human being from without. It multiplies within the person himself. That a particular situation in time brings forth those subjects intended for it is to be taken very literally. Nor are those who produce culture secure before the "increasingly organic composition of mankind".'

The objective tendency, produced by subjects and only transformable by subjects, nevertheless constricts the forms and modes of subjectivation: this dialectic, precisely, generates the perennial catastrophe. And as already noted, these tendencies do not stop short before the physical reduction and liquidation of actual subjects. ‘Genocide is the absolute integration.’[***] Genocide, then, cannot be dismissed as a deviation from the rule of law and humanist norms, for it belongs to the immanent drift of the global process. And after the demonstrations of Auschwitz and Hiroshima, we must live in a social world in which the final integration – the global termination of systemic logic that would at the same time terminate all life and the conditions of all systems – has become objectively possible. Exit, ruined, the myth of progress.

Terror and late capitalism, then, go together. What begins as the pressure of conformity and the market – today, the terrors of precarity and the miseries of austerity – tends toward the logic of exterminism. In the last pages of ‘The Schema of Mass Culture’, Adorno elaborates the connection between the ‘anxiety, that is the ultimate lesson of the fascist era’ and techno-power in the hands of administration:

'The terror for which the people of every land are being prepared glares ever more threateningly from the rigid features of these culture-masks: in every peal of laughter we hear the menacing voice of extortion and the comic types are legible signs which represent the contorted bodies of revolutionaries. Participation in mass culture itself stands under the sign of terror.'

The conformity and resignation fostered by a system of cultural uniformity is connected, through the mediations of an unfolding master logic, to the defeats of radical struggles and the triumphs of capitalist war machines. State terror, resurgent today, declares the bogus ‘war on terror.’

Enjoyment and Enforcement

Another way to think about subjectivation is through Jacques Lacan’s notion of jouissance or enjoyment. I began by détourning the title of a 1992 book by Slavoj Žižek. Other Lacanian theorists have produced stilumating recent work on the problem of ‘commanded enjoyment’, a term introduced by Todd McGowan and helpfully elaborated by Yannis Stavrakakis in his The Lacanian Left. Enjoyment, a form of pleasure that does not necessarily exclude pain, displeasure or even terror, compensates for impotence. The subjective investment in fantasmatic object choices and identifications is not experienced as a conflict with objective reality because enjoyment as it were flies under the radar of conscious reason. This embodied return on investment offers a compelling, if partial, account of our social ‘stuckness’ – our inability to resist our addiction to social processes we know, on another level of awareness, to be self-threatening. The notion of commanded enjoyment acknowledges that the repressed also returns, however, as the hidden cost, the element of unfreedom and compulsion. However indirectly, terror haunts enjoyment issued as a social imperative.

If enjoyment is one side of the coin, then, what we can call enforcement is the other. Enforcement, as I have been developing this concept, is the irreducible element of violence in capitalist reproduction. What begins as the asymmetry of antagonistic productive relations is channeled and intensified, through market competition and imperialist rivalries, into a global process that requires and culminates in war and state terror. The concentration of executive power and the rise of the national security-surveillance state, with its nuclear arsenals of mass destruction and rapidly expanding squadrons of terminator drones – these social processes mutating the capitalist state and hollowing out the carcass of democracy are the continuing condensations of what Adorno called integration and administration. As an unfolding master logic, capitalism has proved to be a self-driving terror machine. We know over whom and what it drives.

In this light, coercion and the paradigm of discipline and punish have not been superseded so much as driven deeper into the structures of everyday subjectivity. Demonstrations of terror, from water-boarding and the dirty war technics of disappearing enemies to the ‘shock and awe’ of spectacular weaponry, show what is done to those who rebel or directly oppose the system. Absorbing the lesson in their bodies, spectators do not need to think twice about it. Terror pre-forms subjectivity and saturates labor relations within the cultural sector as everywhere else, but also circulates as the shadow or reflected presence, as insidious as it is demoralizing, of the real war machines globally in perpetual motion.

Moreover, the celebratory discourses of the creative industries, countersigned by the smirks of pseudo-bohemians, are giving cover to cultural trends that are alarming indeed. Hiroshima had already demonstrated the tendency for science and war machine to merge under the administrations of dominant states. What can be seen today, in company with the politics of fear and the increasing militarization of everyday life, is the merger of war machine and culture industry. Deployments of state terror are accompanied every step of the way by machines of image and spin; these sell the wars that never end by rendering them supremely enjoyable. More and more often, their operators are ‘creatives’ co-opted from the culture industry. The big-money world of bellicose computer gaming – dominated by the Pentagon-funded America’s Army and its commercial rival, Modern Warfare 2 – is one case in point. The career of Adrian Lamo, the convicted ex-hacker turned snitch for Homeland Security, is another: in 2010, Lamo informed on US Army Private Bradley Manning, who allegedly had leaked a damning video of a 2007 massacre of civilians by US forces in Iraq. The first case indicates the addictive power of enjoyment; the second, the corrupting effects and reach of enforcement.

Another way to think about subjectivation is through Jacques Lacan’s notion of jouissance or enjoyment. I began by détourning the title of a 1992 book by Slavoj Žižek. Other Lacanian theorists have produced stilumating recent work on the problem of ‘commanded enjoyment’, a term introduced by Todd McGowan and helpfully elaborated by Yannis Stavrakakis in his The Lacanian Left. Enjoyment, a form of pleasure that does not necessarily exclude pain, displeasure or even terror, compensates for impotence. The subjective investment in fantasmatic object choices and identifications is not experienced as a conflict with objective reality because enjoyment as it were flies under the radar of conscious reason. This embodied return on investment offers a compelling, if partial, account of our social ‘stuckness’ – our inability to resist our addiction to social processes we know, on another level of awareness, to be self-threatening. The notion of commanded enjoyment acknowledges that the repressed also returns, however, as the hidden cost, the element of unfreedom and compulsion. However indirectly, terror haunts enjoyment issued as a social imperative.

If enjoyment is one side of the coin, then, what we can call enforcement is the other. Enforcement, as I have been developing this concept, is the irreducible element of violence in capitalist reproduction. What begins as the asymmetry of antagonistic productive relations is channeled and intensified, through market competition and imperialist rivalries, into a global process that requires and culminates in war and state terror. The concentration of executive power and the rise of the national security-surveillance state, with its nuclear arsenals of mass destruction and rapidly expanding squadrons of terminator drones – these social processes mutating the capitalist state and hollowing out the carcass of democracy are the continuing condensations of what Adorno called integration and administration. As an unfolding master logic, capitalism has proved to be a self-driving terror machine. We know over whom and what it drives.

In this light, coercion and the paradigm of discipline and punish have not been superseded so much as driven deeper into the structures of everyday subjectivity. Demonstrations of terror, from water-boarding and the dirty war technics of disappearing enemies to the ‘shock and awe’ of spectacular weaponry, show what is done to those who rebel or directly oppose the system. Absorbing the lesson in their bodies, spectators do not need to think twice about it. Terror pre-forms subjectivity and saturates labor relations within the cultural sector as everywhere else, but also circulates as the shadow or reflected presence, as insidious as it is demoralizing, of the real war machines globally in perpetual motion.

Moreover, the celebratory discourses of the creative industries, countersigned by the smirks of pseudo-bohemians, are giving cover to cultural trends that are alarming indeed. Hiroshima had already demonstrated the tendency for science and war machine to merge under the administrations of dominant states. What can be seen today, in company with the politics of fear and the increasing militarization of everyday life, is the merger of war machine and culture industry. Deployments of state terror are accompanied every step of the way by machines of image and spin; these sell the wars that never end by rendering them supremely enjoyable. More and more often, their operators are ‘creatives’ co-opted from the culture industry. The big-money world of bellicose computer gaming – dominated by the Pentagon-funded America’s Army and its commercial rival, Modern Warfare 2 – is one case in point. The career of Adrian Lamo, the convicted ex-hacker turned snitch for Homeland Security, is another: in 2010, Lamo informed on US Army Private Bradley Manning, who allegedly had leaked a damning video of a 2007 massacre of civilians by US forces in Iraq. The first case indicates the addictive power of enjoyment; the second, the corrupting effects and reach of enforcement.

These reflections suggest that a break with the master logic of accumulation entails disarming the technocratic national security-surveillance state, and above all the US war machine that is the main enforcer of the global imperialist process. To put it more pointedly: without disarmament, the prospect of emancipating system change is nill. Possibilities for transformation would increase in pace with progressive disarmament, however, and indeed the latter would measure the former. If this is so, then struggles will be strategic only insofar as they articulate themselves with anti-militarist struggles and make their own the aim of dismantling state war machines. Disarmament implies confronting the neo-imperialist state and need not be naïvely pacifist, but obviously this confrontation cannot take the form of a suicidal war of annihilation. Total struggle, mirroring total war, is terminal: pursued without limit or reserve it becomes the terror it aims to fight. And yet effective struggles need to be grounded in everyday experience; they are robust and resilient insofar as they are lived fully and vividly, pulsing beyond a mere convenience emptied of risk. The tight-wires of practice are strung under tension across these aporias. In our world of normalized emergency, the desire to be liberated from fear and terror is the long, gently bowed balancing pole of sanity.

The traversing refusal of imposed fear and terror has clear aims to struggle for: the immediate cessation of all military occupations and interventions and the permanent closure of the global network of neo-imperialist military bases and spy stations that supports them; the global abolition of nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction, without exception; the radical reduction of military spending and the redirection of these funds to the urgent amelioration of social misery. Every real step toward these aims would already be radical change. And only by passing through them can struggles for autonomy, happiness and the liberation of nature have their chance to survive and grow fruitful. There is no liberation within the politics of fear: liberation as such begins and is coextensive with liberation from state terror.

The traversing refusal of imposed fear and terror has clear aims to struggle for: the immediate cessation of all military occupations and interventions and the permanent closure of the global network of neo-imperialist military bases and spy stations that supports them; the global abolition of nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction, without exception; the radical reduction of military spending and the redirection of these funds to the urgent amelioration of social misery. Every real step toward these aims would already be radical change. And only by passing through them can struggles for autonomy, happiness and the liberation of nature have their chance to survive and grow fruitful. There is no liberation within the politics of fear: liberation as such begins and is coextensive with liberation from state terror.

Conclusion

Theories of subjectivation that do not give due weight to the objective factor of a dominating global logic risk lapsing into voluntarism. Those that do will have to face and grapple with the tendencies Adorno pointed to. Strategic resistance begins by assessing the preconditions for its own actual effectiveness. Unhappily, developments since Dialectic of Enlightenment have not yet refuted its case. But if we cannot make our history just as we like, oblivious to inherited constraints, we can always transform our pessimism by organizing and aiming it, as both Benjamin and Gramsci counseled at the dawn of the new terror.

Theories of subjectivation that do not give due weight to the objective factor of a dominating global logic risk lapsing into voluntarism. Those that do will have to face and grapple with the tendencies Adorno pointed to. Strategic resistance begins by assessing the preconditions for its own actual effectiveness. Unhappily, developments since Dialectic of Enlightenment have not yet refuted its case. But if we cannot make our history just as we like, oblivious to inherited constraints, we can always transform our pessimism by organizing and aiming it, as both Benjamin and Gramsci counseled at the dawn of the new terror.

[*] As we now know, processes of ‘new enclosure’ in China and India have actually resulted in a massive increase in the size of the planet’s industrial proletariat. These new ‘direct producers’ of commodities work in factories and sweatshops that combine elements of Fordist and pre-Fordist (in fact nineteenth-century) forms of organization and discipline. Evidently, the new ideal-typical worker is a young or teenage woman who has been separated from her family and social networks for the first time and who sends home the bulk of her earnings. These vulnerable workers, who may be charged with pay cuts for talking on the work floor or socializing off-hours with members of the opposite sex, clearly do not fit the model of post-Fordist virtuoso. Moreover, their terms of employment are precarious in the extreme; they have been largely stripped of representation and Fordist securities and can be fired at will. For a chilling glimpse into the new factory, see David Redmon’s 2005 documentary film Mardi Gras: Made in China.

[**] The scintillation of these lines begs comment. The alignment of ad-saturated pop culture (neon signs) with mystification (comet reading, or astrology) becomes a negative evocation of arcing V-2 rockets and aerial bombing – a prefiguring echo of the famous first line of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (‘A screaming comes across the sky.’) While I will not remark it further, the oblique allusion to terror will be relevant to the last two sections of the essay.

[***] The passage from Negative Dialectics continues: ‘It is on its way wherever people are leveled off [gleichgemacht werden] – ‘polished off’ [geschliffen], as they called it in the military – until one exterminates them literally, as deviations from the concept of their utter nullity. Auschwitz confirmed the philosopheme of pure identity as death.’

[**] The scintillation of these lines begs comment. The alignment of ad-saturated pop culture (neon signs) with mystification (comet reading, or astrology) becomes a negative evocation of arcing V-2 rockets and aerial bombing – a prefiguring echo of the famous first line of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (‘A screaming comes across the sky.’) While I will not remark it further, the oblique allusion to terror will be relevant to the last two sections of the essay.

[***] The passage from Negative Dialectics continues: ‘It is on its way wherever people are leveled off [gleichgemacht werden] – ‘polished off’ [geschliffen], as they called it in the military – until one exterminates them literally, as deviations from the concept of their utter nullity. Auschwitz confirmed the philosopheme of pure identity as death.’

No comments:

Post a Comment