It’s too easy, White warns us, to simply dismiss Hirst, through an annihilating critique that fails to confront the real fascination operating in his art.

Point taken. And White’s discussion of the antagonisms staged in For the Love of God is strong and convincing. To make these antagonisms visible and available to reflection already pierces its glittering halo, without failing to give the devil his due.

My reservation: today the link between capital and death is even deeper than White registers. Capital has become in actual fact what it always was potentially: a techno-genocidal automaton busily destroying the very conditions of life. Or rather, and more horribly, compelling each of us to contribute to this process, and thus surrender, every day of our lives.

What speaks mutely in many of Hirst’s works is a coldness, an absence of life and warmth – the coldness of an objective process we have for decades been helpless to restrain or change.

There was a moment in postwar culture when this coldness was mirrored effectively as a critical artist means. That was the bite of dissonant modernism. But compared to Hirst, even Beckett’s stare is a warm and compassionate protest.

There is no protest to Hirst’s coldness. It mirrors, but without a trace of that passion or compassion that leads us back to each other in urgency. This lack of heart, this absent clenched fist of humane outrage at our present impotence, is the missed encounter at the heart of Hirst’s work. It marks not just Hirst’s failings as an individual artist, but the crystallized failure of a whole historical moment.

Needing heart, needing warmth, as well as honesty and truth, from anything that would call itself art, now more than ever, what shall we say to or about skulls that leave us “blinking, dazzled, and bemused” but not warmed or more human?

Speaking of Hirst, should we not ask this, as well?

“The yawning jaws, the wreathed lips, the enormous teeth, the bulging eyes, composed a striking death’s-head....The mule, in his opinion, had died of old age. He had bought it, two years before, on its way to the slaughterhouse. So he could not complain. After the transaction the owner of the mule predicted that it would drop down dead at the first ploughing. But Lambert was a connoisseur of mules. In the case of mules, it is the eye that counts, the rest is unimportant. So he looked the mule full in the eye, at the gates of the slaughterhouse, and saw that it could still be made to serve. And the mule returned his gaze, in the yard of the slaughterhouse....I thought I might screw six months out of him, said Lambert, and I screwed two years.”

Beckett, Malone Dies, 1952/56.

Point taken. And White’s discussion of the antagonisms staged in For the Love of God is strong and convincing. To make these antagonisms visible and available to reflection already pierces its glittering halo, without failing to give the devil his due.

My reservation: today the link between capital and death is even deeper than White registers. Capital has become in actual fact what it always was potentially: a techno-genocidal automaton busily destroying the very conditions of life. Or rather, and more horribly, compelling each of us to contribute to this process, and thus surrender, every day of our lives.

What speaks mutely in many of Hirst’s works is a coldness, an absence of life and warmth – the coldness of an objective process we have for decades been helpless to restrain or change.

There was a moment in postwar culture when this coldness was mirrored effectively as a critical artist means. That was the bite of dissonant modernism. But compared to Hirst, even Beckett’s stare is a warm and compassionate protest.

There is no protest to Hirst’s coldness. It mirrors, but without a trace of that passion or compassion that leads us back to each other in urgency. This lack of heart, this absent clenched fist of humane outrage at our present impotence, is the missed encounter at the heart of Hirst’s work. It marks not just Hirst’s failings as an individual artist, but the crystallized failure of a whole historical moment.

Needing heart, needing warmth, as well as honesty and truth, from anything that would call itself art, now more than ever, what shall we say to or about skulls that leave us “blinking, dazzled, and bemused” but not warmed or more human?

Speaking of Hirst, should we not ask this, as well?

“The yawning jaws, the wreathed lips, the enormous teeth, the bulging eyes, composed a striking death’s-head....The mule, in his opinion, had died of old age. He had bought it, two years before, on its way to the slaughterhouse. So he could not complain. After the transaction the owner of the mule predicted that it would drop down dead at the first ploughing. But Lambert was a connoisseur of mules. In the case of mules, it is the eye that counts, the rest is unimportant. So he looked the mule full in the eye, at the gates of the slaughterhouse, and saw that it could still be made to serve. And the mule returned his gaze, in the yard of the slaughterhouse....I thought I might screw six months out of him, said Lambert, and I screwed two years.”

Beckett, Malone Dies, 1952/56.

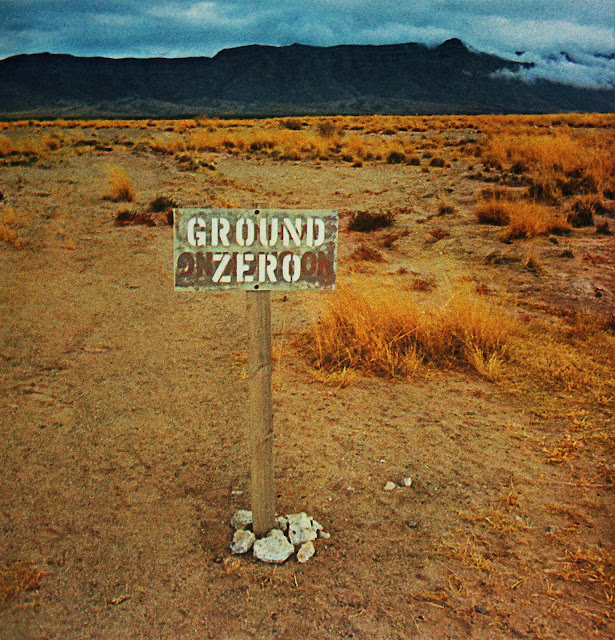

(Photo: Damien Hirst, A Thousand Years, 1990)

Thanks for these really interesting comments on my essay. There is one thing that I would add to your argument that the skull is without human warmth: one of the most disturbing things for me is the rhetoric of Hirst's publicity machine, which often in fact promotes the work precisely in terms of a form of transcendence through beauty – an assertion of life in the face of death. This is, I think, largely a bogus claim, but in many ways I am relieved that it is. The skull itself is capitalist art become directly murderous in the way that you note that capitalism itself has become directly genocidal: the diamond mining industry is a particularly unpleasant one, in which in many places people labour as subcontractors without any guarantee of pay, within monopoly conditions in which the buyer has an absolute ability to dictate the terms of the deal. Even for those finding diamonds, pay is usually below subsistence levels - only better than starving to death more quickly (many people working as miners are displaced farmers). It's not the spectacular horror of the gold mines which Sebastiao Salgado has photographed, but it is ultimately just as terrible. Given this (and given that the resources of diamond fields are also often a fuel for war and civil war), for Hirst to produce a work which transmuted these materials into human warmth and hope (undertaking a form of aesthetic redemption) would seem to me to be throwing us onto the ground of Adorno's famous dictum about art after Auschwitz. To find redemption within this becomes obscene...

ReplyDeleteThis is not to say that we do not need an art and a culture which supplies us with a human warmth beyond the deathliness of capital - an art which takes us beyond the deadlock of Adorno's dictum (a matter about which I know you have had much to say!). And of course, Hirst does not offer us this, as you note. This would seem to me to mark the line between (Hirstean) capitalist art and what a truly "radical" art might do. For a capitalist art to offer warmth, transcendence or the like will always be a kind of ideological gloss over its underlying heartlessnees - the liberal illusion. If it does not take the step to a properly radical position, then for me at least, it's better that it doesn't offer us that kind of false reconciliation, at least.

Luke

Luke, this helps and clarifies. What measuring with the thermometer I far too quickly called "warmth" would have to be more and different than the cheap sentimentalism peddled by the culture and affect industries. What I was groping to grip there was the difference between Beckett's notorious "coldness" and the taste that Hirst leaves in the mouth. Beckett's mirroring, tough as it is, always registers a protest that, at day's end, is difficult to talk about in anything other than a humanist language. (One has to be humane enough to be outraged.) Here, talking about Hirst, I'm not interested in the old disputes over "humanism." I'll subscribe to a critical humanism, along with a critical Marxism, in order to think and talk about what's damningly missing from Hirst's art. I agree with you that the alternative cannot be a lapse into false reconciliation. And so I think you've put your finger right on it, when you emphasize this category of "capitalist art," implying a mutation from the relative autonomy of dissonant modernism.

ReplyDeleteThe difference between Beckett's mirroring and Hirst's may be hard to pin down precisely. I can't be sure I'm not projecting it, but if it is more than readerly projection, then it shows us how far artistic autonomy has been compromised by the pressures of art market and culture industry since the 1950s, more or less as Adorno predicted. Maybe ambitiously accommodating "capitalist art" is compelled to make Hirst's bargain, but such ambitions themselves can after all be refused. There's still enough claimable operative autonomy there to provide cover for something far more critical - for an art with more "heart" (another poor metaphor that I'll take on board in this context, with lashes) in its rigor. The context and audience for an art of critically sublime dissonance certainly have changed a lot, in ways that matter for what happens in reception situations. But I'll wager it's still possible to produce good (radical) effects of this kind. On that ground, for me, Hirst can't get off the hook.

What my position probably fails to grapple enough with, is the powerful fascination Hirst's kind of mirroring mobilizes -- what Yannis Stavrakakis in a Lacanian idiom calls "commanded enjoyment." Maybe on the field of jouissance, the (now old) Adornian sublime can no longer compete with the libido-luring fantasies Hirst toys with?

Needing heart, needing warmth, as well as honesty and truth, from anything that would call itself art, now more than ever, what shall we say to or about skulls that leave us “blinking, dazzled, and bemused” but not warmed or more human?

ReplyDeleteOk, it's obvious that Hirst's image is a double edged sword. We can turn this defiant gesture into a constructive cipher. The thrust of the image must address what it depicts: Not man-to-man exploitation, but man-to-animal, man-to-nature exploitation.

How can aesthetic discourse shake its heavily anthropocentric view of nature?

On the right, too much complacency with formalisms, abstractions, aestheticisms, on the left, the deferring of a more ecological view of aesthetics, one that addresses ecosystemic balance, technological violence, instrumentalism, human "development," the value of animal life, animal rights, etc.

Well put, AT. Let's explore your notion of "a more ecological view of aesthetics" - one certainly is needed. The techno-domination of "nature, internal and external" has overwhelmed politics and ethics. To grasp why and figure out what to do about it is as urgent as it gets. But what would an aesthetics be that undoes this domination? A politicized erotics? I'd love to hear more about it...

ReplyDeleteOne constraint on such an aesthetics, maybe, is that our senses, our experiences of sensuous nature, are themselves damaged and transformed by this dominant social logic of domination. We have to learn how to "see" and "feel" with a different logic, since we evidently can't see what we need to see.

Of course, we're not damned to a helpless blindness in this regard, but to liberate nature (and not aestheticize about its possible liberation) would mean solving the political problem of constraining the logic of accumulation, wouldn't it? Aesthetics is a promise, but one that points to the persisting gap between what we might be able to feel subjectively and the continuing objective meltdown.

I doubt we can return to a direct, immediate, socially unmediated relation to "nature." But we certainly can relate to the biosphere and the animals we share it with in a less dominating and exploitative way. Can we do it within capitalism?

We have to learn how to "see" and "feel" with a different logic, since we evidently can't see what we need to see.

ReplyDeleteIndeed, particularly because there is no "seeing" without "feeling."

For me at least, it means "distancing" myself from the exigencies of foundations, whether epistemic, political, ideological, ethical or otherwise.

The "distancing" is methodological, not a ploy to avoid confrontation or hard choices, but for the sake of eliminating the overflow of empty static (what some call self-deceit). Nature (including non-sentient beings), must become more than a means-to-an-end to man.

Jehan: I wouldn't wait for Capitalism to end to try changing my self and the ones around me.

Thanks, AT. No, let’s not wait for capitalism to end, before trying... But let’s not disavow the problem of capitalist power, either.

ReplyDeleteEverything passes through personal practice, the subjective, call it what you like. Yes, all kinds of “distancing” (as you call it) techniques can shift and intensify the forms of subjective focus and produce new or different experiences. Even a dilettante like me can attest to that. But these dissolutions and shiftings of the subject-object relation, changing as they may be, do not make either subject or object disappear, returning us to the fullness of a lost and longed for immediacy. You take your “foundations” – and your history (scars, traumas, obsessions) and social position – with you wherever you wander. You can disavow these mediations, but that doesn’t release you from their power. (I’m sorry if that sounds like a predictable response…)

Joel Kovel’s point about it, at the end of Against the state of Nuclear Terror, is that the struggle to change our relations to each other and the world don’t have to exclude this kind of questing. But objective reality always operates as a constraint and imposes the context of struggle on us, like it or not. As this reality has already become genocidal and ecocidal in ways that threaten to be terminal, some of us will think it’s not enough to stand on our heads or fiddle while Rome burns (or the oil spills, again). So the challenge is to politicize what is basically an erotics – a fully embodied practice of enjoyment – in helpful, effective, careful ways. There are many possibilities in that direction, obviously.

It's been decades since Allen Ginsberg tried to levitate the Pentagon with good will, meditation and chanting, but I doubt that is what ended the Vietnam War...

But you know all this, so you may have left me behind for a while.

GR

Agree on capitalism!

ReplyDeleteBut it would be pure wishful thinking to pretend that once capitalism is gone we'll move into the singularity of paradise. We'll build ourselves with yet another economic simulacrum to betray, abuse and kill one another. As you say, all the phantasms keep coming: Cain's hate, Judas' betrayal, Rousseau's greed, Phthonus' envy , Hobbes' brute nature, Nietzsche's slave morality.

What is it? No doubt a marked inclination, a obstinate symptom that keeps surfacing like a constant, glued to human choice and volition. That's the avidya of the Vedanta. A structural condition of our core humanity. Take that to the public & political realms and you get (p)olitics! You get (c)apitalism!

GR: I'm only filled with doubts.