Ecology and

Revolution

By Herbert Marcuse

(from Liberation 16 (September 1972):10-12)

Coming from the

United States, I am a little uneasy discussing the ecological movement, which

has already by and large been co-opted [there]. Among militant groups in the

United States, and particularly among young people, the primary commitment is

to fight, with all the means (severely limited means) at their disposal,

against the war crimes being committed against the Vietnamese people. The

student movement – which had been proclaimed to be dead or dying, cynical and

apathetic – is being reborn all over the country. This is not an organized opposition

at all, but rather a spontaneous movement which organizes itself as best it

can, provisionally, on the local level. But the revolt against the war in

Indochina is the only oppositional movement the establishment is unable to

co-opt because neocolonial war is an integral part of that global

counterrevolution which is the most advanced form of monopoly capitalism.

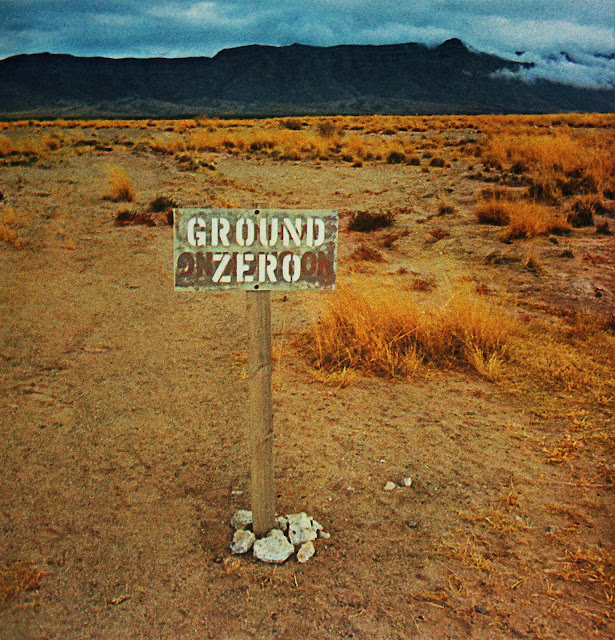

So, why be concerned

about ecology? Because the violation of the earth is a vital aspect of the

counterrevolution. The genocidal war against people is also “ecocide” insofar

as it attacks the sources and resources of life itself. It is no longer enough

to do away with people living now; life must also be denied to those who aren’t

even born yet by burning and poisoning the earth, defoliating the forests,

blowing up the dikes. This bloody insanity will not alter the ultimate course

of the war, but it is a very clear expression of where contemporary capitalism

is at: the cruel waste of productive resources in the imperialist homeland goes

hand in hand with the cruel waste of destructive forces and consumption of

commodities of death manufactured by the war industry.

In a very specific

sense, the genocide and ecocide in Indochina are the capitalist response to the

attempt at revolutionary ecological liberation: the bombs are meant to prevent

the people of North Vietnam from undertaking the economic and social

rehabilitation of the land. But in a broader sense, monopoly capitalism is

waging a war against nature – human nature as well as external nature. For the

demands of ever more intense exploitation come into conflict with nature

itself, since nature is the source and locus of the life-instincts which

struggle against the instincts of aggression and destruction. And the demands

of exploitation progressively reduce and exhaust resources: the more capitalist

productivity increases, the more destructive it becomes. This is one sign of

the internal contradictions of capitalism.

One of the essential

functions of civilization has been to change the nature of man and his natural

surroundings in order to “civilize” him – that is, to make him the

subject-object of the market society, subjugating the pleasure principle to the

reality principle and transforming man into a tool of ever more alienated

labor. This brutal and painful transformation has crept up on external nature

very gradually. Certainly, nature has always been an aspect (for a long time

the only one) of labor. But it was also a dimension beyond labor, a symbol of beauty, of tranquility,

of a non-repressive order. Thanks to these values, nature was the very negation

of the market society, with its values of profit and utility.

However, the natural

world is a historical, a social world. Nature may be the negation of aggressive

and violent society, but its pacification is the work of man (and woman), the

fruit of his/her productivity. But the structures of capitalist productivity is

inherently expansionist: more and more, it reduces the last remaining natural

space outside the world of labor and of organized and manipulated leisure.

The process by which

nature is subjected to the violence of exploitation and pollution is first of

all an economic one (an aspect of the mode of production), but it is a

political process as well. The power of capital is extended over the space for

release and escape represented by nature. This is the totalitarian tendency of

monopoly capitalism: in nature, the individual must find only a repetition of

his own society; a dangerous dimension of escape and contestation must be

closed off.

At the present stage

of development, the absolute contradiction between social wealth and its

destructive use is beginning to penetrate people’s consciousnesses, even in the

manipulated and indoctrinated conscious and unconscious levels of their minds.

There is a feeling, a recognition, that it is no longer necessary to exist as

an instrument of alienated work and leisure. There is a feeling and a

recognition that well-being no longer depends on a perpetual increase in

production. The revolt of youth (students, workers, women) undertaken in the

name of the values of freedom and happiness, is an attack on all the values

which govern the capitalist system. And this revolt is oriented toward the

pursuit of a radically different natural and technical environment; this

perspective has become the basis for subversive experiments such as the

attempts by American “communes” to establish non-alienated relations between

the sexes, between generations, between man and nature – attempts to sustain

the consciousness of refusal and of renovation.

In this highly

political sense, the ecological movement is attacking the “living space” of

capitalism, the expansion of the realm of profit, of waste production. However,

the fight against pollution is easily co-opted. Today, there is hardly an ad

which doesn’t exhort you to “save the environment,” to put an end to pollution

and poisoning. Numerous commissions are created to control the guilty parties.

To be sure, the ecological movement may serve very well to spruce up the

environment, to make it pleasanter, less ugly, healthier and hence, more

tolerable. Obviously, this is a sort of co-optation, but it also [contains] a

progressive element because, in the course of this co-optation, a certain

number of needs and aspirations are beginning to be expressed within the very

heart of capitalism and a change is taking place in people’s behavior,

experience, and attitudes towards their work. Economic and technical demands

are transcended in a movement of revolt which challenges the very mode of

production and model of consumption.

Increasingly, the

ecological struggle comes into conflict with the laws which govern the

capitalist system: the law of increased accumulation of capital, of the

creation of sufficient surplus value, of profit, of the necessity of

perpetuating alienated labor and exploitation. Michel Bosquet put it very well:

the ecological logic is purely and simply the negation of capitalist logic; the

earth can’t be saved within the framework of capitalism, the Third World can’t

be developed according to the model of capitalism.

In the last

analysis, the struggle for an expansion of the world of beauty, nonviolence and

serenity is a political struggle. The emphasis on these values, on the

restoration of the earth as a human environment, is not just a romantic,

aesthetic, poetic idea which is a matter of concern only to the privileged;

today, it is a question of survival. People must learn for themselves that it

is essential to change the model of production and consumption, to abandon the

industry of war, waste and gadgets, replacing it with the production of those

goods and services which are necessary to a life of reduced labor, of creative

labor, of enjoyment.

As always, the goal

is well-being, but a well-being defined not by ever-increasing consumption at

the price of ever-intensified labor, but by the achievement of a life liberated

from the fear, wage slavery, violence, stench and infernal noise of our

capitalist industrial world. The issue is not to beautify the ugliness, to

conceal the poverty, to deodorize the stench, to deck the prisons, banks and

factories with flowers; the issue is not the purification of the existing

society but its replacement.

Pollution and

poisoning are mental as well as physical phenomena, subjective as well as

objective phenomena. The struggle for an environment ensuring a happier life

could reinforce, in individuals themselves, the instinctual roots of their own

liberation. When people are no longer capable of distinguishing between beauty

and ugliness, between serenity and cacophony, they no longer understand the

essential quality of freedom, of happiness. Insofar as it has become the

territory of capital rather than of man, nature serves to strengthen human

servitude. These conditions are rooted in the basic institutions of the

established system, for which nature is primarily an object of exploitation for

profit.

This is the

insurmountable internal limitation of any capitalist ecology. Authentic ecology

flows into a militant struggle for a socialist politics which must attack the

system at its roots, both in the process of production and in the mutilated

consciousness of individuals.

No comments:

Post a Comment