|

| Arman, untitled combustion, 1964 |

Plight of the After: Further Notes on Cage,

Silence, Arman, Beuys, Adorno, Beckett, Trauma, Rememoration and Negative

Presentation in Post-1945 Visual Art

by Gene Ray

|

| Beuys, Plight, 1985 |

Two works by Joseph Beuys,

or more precisely, two contrasting moments in his output: the first, a proposal

for a Holocaust memorial produced in 1958, a feeble misfire; the second, the

installation Plight, made and

exhibited in 1985, a forcefully effective work of historical avowal. These two

moments document the impressive development of one German artist. But more than

that, they indicate the whole painful struggle within the visual arts to

confront and respond to the Nazi genocide, a crime of state terror for which

the place-name ‘Auschwitz’ has come synecdochically to stand. For visual

artists willing to risk such a confrontation, the means and strategies with

which to do so were by no means clear or obvious in 1958; if, after 1985, such

means and strategies were established and available, that was due to the work

of many, in a collective development that was absorbed and synthesized in Plight.

Beuys’ proposal for a

memorial at Auschwitz-Birkenau, submitted in March 1958 to the juried

competition organized by an association of camp survivors, was a failure by any

standard. His offer to overshadow the camp with a monumental ‘monstrance’ derived

from Roman Catholic ritual was wildly, monstrously inappropriate. I register

this moment of misfire only to establish Beuys’ relatively early concern with

the meaning, legacy and representation of Auschwitz. Beuys was one of 426

artists who submitted proposals to the jury convened in 1956 by the Comité

international d’Auschwitz. For it, he produced numerous drawings and models in

wood, pewter and zinc. None are compelling or evince much insight. Some were

later incorporated into various installations and vitrines, including Auschwitz

Demonstration 1956-1964; the dates

in the title of the latter indicate the artist’s retrospective desire to

establish his continuous engagement with the Nazi genocide and the problem of

its artistic representation. This desire is significant, especially given

Beuys’ evident reticence with regard to Nazism and its crimes. These early

sketches and models, loaded with the Christian symbolism of sin, guilt,

sacrifice and forgiveness, may betray the stirrings of the artist’s own

unresolved conflicts in facing this history. They certainly illuminate a

profound confusion before the crisis of representation imposed on art ‘after

Auschwitz’, to use the phrase of Theodor W. Adorno. This confusion was hardly

unique at the time; it marks a moment when the dialectic between genocidal

history and representation was felt by some European visual artists as the

pressure of a still unclarified problematic.

|

| Beuys, Auschwitz Demonstration, 1964 |

The negative presentation

of Auschwitz through the indirect material linkages and evocative strategies

deployed so effectively in Plight

– the environment he installed in the London gallery of Anthony d’Offay in 1985

– was only possible after the investigation of negative presentation in the

visual arts had reached a certain point of development. The artistic strategy

evident in this work manifests an understanding of the potentials of negative

evocation to respond to historical trauma and catastrophe, as well as an at

least minimally conscious control of the sculptural means for such evocation.

With regard to artistic means, all the techniques used by Beuys in Plight had probably been developed by other artists by

the end of 1961, although their potentials would not have been immediately

clear to all.[1] The necessary historical disclosures no doubt took longer to

circulate and fully sink in; the critical processing of those disclosures is by

no means complete today.

Plight is a culminating work, in the precise sense that

it consolidates this collective investigation and development that took place

in the visual arts between 1945 and the end of 1961 in a way so compelling that

it establishes a new standard for artistic approaches to Auschwitz. The

negative memorials that in the 1990s would become the institutionally preferred

model for monumental public remembrance are prefigured by Plight and are, by and large, merely echoes or variations

on it. I am not concerned in this essay to treat Beuys’ personal development or

career in any detail, beyond what I have done elsewhere.[2] Here I focus on Plight, in order to unfold from this one work the

outlines of a larger history – the discovery and development, in the visual

arts, of negative, dissonant strategies for representing catastrophic history

in the aftermath of World War II.

Any such outline

necessarily takes up problems articulated after 1945 by critical theory,

namely, the very specific predicament or indeed plight of art ‘after Auschwitz.’

Critical reflection on the meaning and implications of Auschwitz, and indeed on

the whole social context of violence that produced it, emerged and circulated

relatively slowly. Of the few sustained reflections in the early postwar

period, only Adorno’s attempted to articulate fully the implications of

Auschwitz for music, literature, philosophy and all forms of serious cultural

production. A detailed study of Adorno’s reception has yet to be written, but

his critique of traditional culture in the aftermath was probably disseminated first

in fragments and echoes. It would be surprising, though, if partial, more or

less distorted forms of Adorno’s complex arguments were not beginning to

penetrate the visual arts in Europe by the late 1950s, given a push no doubt by

the impact of Alain Resnais’ 1955 documentary Nuit et brouillard. Literature and music led the way in developing

new means and strategies for responding to Auschwitz, as even Resnais’ film

confirms: much of the force of Nuit and brouillard comes from the dissonance generated between the

images qua visual evidence and the critical glossing of those images by Jean

Cayrol’s voice-over text and Hanns Eisler’s score. Indeed, Adorno’s thinking

about dissonance was strongly stimulated by postwar developments in literature,

music and theater. About the visual arts, he wrote relatively little. But as I

show, visual analogues of dissonance and negative presentation emerged in sculpture

and installation art as well beginning in the late 1950s.

The Elements of Plight: Installed Forms, Materials and Objects

Stepping through a doorway

or passage, the spectator enters a rectangular room lined floor to ceiling with

standing felt columns: two columns of equal size stacked vertically, one on the

other, so that two closed ranks of standing columns extend horizontally, wall

to wall. Each constituent column is about a meter and a half in height, and

roughly the volume of a person. The repeated felt forms affect the space as an

echoing lining that both isolates and insulates. Sound from outside is

suppressed, temperature inside is conserved, and light seems to be absorbed by

the rough gray tactility of the felt. Toward the back of the room, an opening

in the lower row of columns on the right wall leads to a second room, also

lined with felt columns. To navigate this opening, most spectators will have to

bend down and pass beneath the upper row of columns. Having gained the second

room, which in the original London installation contained no other openings,

one finds a grand piano.[3] Both its case and keyboard are closed. A chalkboard

lined with musical staves lies flatly on top of the piano; no notes are written

on it. Lying on the staff board is an ordinary fever thermometer. From the dead

end of the second room, the spectator’s line of sight to the outside is severed,

and the suppression of outside sound increases. An L-shaped, felt-columned

cul-de-sac, then, containing three objects.

The wall label or equivalent

signage identifies all this as the work of Beuys, a German artist. A certain

history necessitates that we qualify this nationality rather severely. Beuys

was eleven years old when, through no fault of his own of course, the Reichstag

Fire Decree and Enabling Act of 1933 handed vast powers to the new Nazi

Chancellor and his party. Subsequently, we know, Beuys was a member of the

Hitlerjugend and served in the Wehrmacht. These facts do not permit us to think

of Beuys the artist as just any ‘German’. Encountering or considering his art,

we are enjoined to remember that he was a boy scout and combat veteran of the

Nazi regime. As such, he is indelibly marked as a member of the so-called

perpetrating generation.[4] These facts are not a warrant for arrest. They

cannot be construed in a way that would fix or freeze Beuys beyond any growth

or change, or would deny to him any possibility of critical understanding or agency.

And they certainly do not suffice to indict or automatically discredit his art.

But neither can they be forgotten or blithely avoided. The work is not

reducible to the life, but neither can it be isolated from it, behind a cordon

sanitaire. Beuys’ position within

a certain, extremely violent and disastrous history is a social fact that is

objective in a very unanswerable sense.

The title, Plight, constitutes the artist’s concise statement about

the work. A title is a linguistic tag, hence a conceptual anchor, tied to the

work by a rode of intention. As such, it cannot be read naïvely. ‘Plight’, an

English noun, denotes a dangerous, difficult or unfortunate situation. A verb

form, marked as a secondary meaning of archaic origin, means to make a solemn pledge

or promise. This semantic range points, if it is not ironic or deceptive, to

some danger, difficulty or misfortune still to be specified. Alternatively or

perhaps additionally, there may be some pledge or promise operative in or

activated by the work.

The three objects

installed in the work – piano, staff board and thermometer – are so-called

found objects, the authorized presentation of which in art spaces was long

established by 1985. The selective principles of montage and assemblage reach

back to Cubist collage, which around 1912 first opened the door to invasions of

visual art by bits and pieces of empirical life. Passing through Dada and the

readymades of Duchamp, such object-choices were given additional psycho-erotic

charges by the Surrealists. In the postwar period, empirical reality once again

flowed undigested into works and galleries, this time in the service of

divergently developing artistic agendas that tended, even in their divergence,

to erode the borders between art and life and to subvert the stability of

mimetic representation. The ambiguity and disruptive potential of found objects

have undoubtedly been diluted with institutional acceptance and widespread use;

today their appearance troubles no one. But they still carried some force when,

in the 1950s and 1960s, the arts were overflowing the demarcations of

traditional media and were recombining globally into new streams of pronounced

performativity. Relevant here are Allan Kaprow’s Happenings, largely a movement

of New York painters spurred by the pressure of Jackson Pollock; the Gutai Art

Association of Japanese painters and sculptors; and Fluxus, a network of

composers and poets largely inspired by John Cage and active in Europe. The

latter, along with Nouveau Réalisme, gave strong impetus to Beuys’ artistic

development. If, as we will see, he learned a great deal about the sculptural

possibilities of found objects from Nouveaux Réalistes such as Arman and Daniel

Spoerri, it was through his participation in events organized by or around

Fluxus that Beuys was able to assimilate Cage’s deconstruction of music and to

work out his own more symbolist and allegorical approach to performance.

Beuys has gathered and

configured three specific objects into an assemblage installed in the dead-end

of the felt-walled space. The grand piano and the staff board clearly allude to

music. But the piano is closed and no musical notes have been written on the

staff board. So there is actually no music. Music is evoked by negative

presentation, called in as it were, not by naming but by the selection and

presentation of two found objects with specifically musical associations. Here,

in the installation, the evocation avows that there is, or at least was, music,

at the same time that it refuses, blocks and occludes the actual acoustic

phenomenon of music. The grand piano alludes to concerts and concert halls, the

practice and recital of sonatas. But no sonatas, or any other form of music,

will be performed on this piano. The possibility is foreclosed by the shutting

of the case and keyboard: music as such has been silenced. The staff board, a

pedagogical device, evokes scenes of musical instruction. But the lesson here

is: no notes, no music. Silence and silencing, then, are the common

associations of these musical found objects. Irony? Possibly. But what of the

third object? The household thermometer evokes domestic scenes of illness. Does

silenced music have a temperature or fever? A joke, perhaps? While such

questions cannot yet be answered, their posing is made more insistent by the

sound absorbing and temperature conserving character of the thick felt columns.

Silence and Demolition

It was John Cage, of

course, who famously investigated ambient and found sounds – indeed, the very

sounds of silence audible in the negation of formal or traditional

music. Cage’s best-known composition, the provocative 4’33” (1952) was precisely a score, in three movements

marked tacet, for the performed

silencing of a piano. Experiments with an anechoic chamber in 1951 convinced

Cage that so-called silence does not really exist. Music, he was proposing by

1955, is a duration of intended sounds and silences, while what we call silence

is merely all the sounds we do not intend.[5]

Perhaps because Cage

himself exuded a benign and serene gentleness and great personal generosity,

the violence of his gestures vis-à-vis the Western musical tradition often goes

unremarked. His experiments and compositions for prepared piano, dating back to

1938 or 1939 but intensifying between 1942 and 1948, enact mutilating

interventions on the piano qua traditional instrument. Notes and harmonies are

in effect disappeared and deflected into new and uncanny sounds, through the

distorting insertion of screws, bolts, weather stripping and other objects and

materials between the piano strings. Cage, a former student of Arnold

Schoenberg, was schooled in dissonance. But his investigations of ambient and

chance sounds eschew even that tradition. His subversion of artistic intention,

linking up to heretical streams of automatism and aleatory gaming, goes far

beyond the rigorous combinations of twelve-tone composition. With regard to the

whole context of traditional music and its performance, Cage is quietly

demolitionist. And his demolitions resound beyond the medium of music as such,

to challenge the other arts as well.

How much more devastating is Cage’s silence, for example, than Duchamp’s

fictional turn to chess and ‘silence’, or the automatic poems of Surrealist

aesthetes.

Cage’s demolitions of

tradition are not usually understood as responses to the violence of World War

II. Such a reading runs against the tenor of Cage’s own words and his well-marked

indifference to history. In an interview published in 1955, Cage refused the

suggestion that his suppression of intention must still maintain some hidden

lyric concern. He flatly cut off the interviewer’s question (‘Do not memory,

psychology – ‘) with a demonstrative ‘—never again.’[6] In a text from three

years later, he repeats this refusal, ventriloquizing Kafka in a question that

nevertheless endorses it: ‘Do you not agree with Kafka when he wrote, “Psychology

– never again”?’[7] If this refusal of memory and psychology, which might be

suspected of protesting too much, reflects an avant-garde grasp of some real

crisis of the subject under pressures of modernity, then, as we will see below,

any such crisis itself throws us back on history. For how else could we explain

it, or an art already looking beyond it? It is the violence of the

mid-twentieth century, Adorno will argue, that demonstrates in specific and

irrefutable ways, the crisis and fate of the autonomous – that is, the lyrical,

psychological – subject.[8]

In the Beckett-like ‘Lecture

on Nothing’, first delivered at the 8th Street Artists Club in New York in 1949

but not published until a decade later, Cage makes a rare but revealing mention

of the war. ‘The most amazing noise // I ever found / was that produced by /

means of a coil of wire / attached to the // pickup arm / of a phonograph and

then / amplified. / It was shocking, // really shocking, / and thunderous / . /

Half intellectually

and // half sentimentally / , when the war came a-long, / I decided to

use / // only / quiet sounds / . /

There seemed to me // to be no truth, / no good, in anything big / in society.’[9]

(The lecture was reprinted in 1961, in Cage’s collected texts, under the title Silence.)

Wars of course do not just ‘come along’, and the close proximity of shock

and thunder, insistently repeated, suggests that it, the war, rather than the

fabricated sound, is what Cage really ‘finds’.[10] These lines, including their

passing naturalization of social violence, can be read symptomatically as the

registration of a general, globalized trauma – one that Cage is

working-through, or better, playing-through, as method, in his opening of a new

line of artistic experiment. In this light it is not irrelevant that 4’33”, first performed by David Tudor at Woodstock in

1952, was conceived in the immediate postwar period, as Cage was working on the

Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano (1946-48). Even his famous turn to Zen and chance did not really begin

until 1946.[11]

Even stronger confirmation

of such a reading is found in the gestures and production of Cage’s students in

and around Fluxus. Clearly understanding something else or more in the master’s

lessons, Nam June Paik, La Monte Young, Benjamin Patterson, George Brecht, Philip

Corner, George Maciunas, Dick Higgins, Emmett Williams and others, including Wolf

Vostell and – yes – Joseph Beuys, radicalized Cage’s relatively subtle and

symbolic demolitions into often aggressive enactments of literal violence and

destruction. Paik was the driving force.[12] In his notorious Étude for

Piano, performed in Cologne in

1960, Paik leapt from the stage and attacked his watching ‘fathers’, Cage and Tudor,

cutting off Cage’s tie and pouring shampoo on both composers before fleeing the

concert. In June of 1962, the symbolic violence was literalized onstage in

Paik’s One for Violin, at the

event Neo-Dada in der Musik in

Düsseldorf. Grasping a violin by the neck with both hands and raising it above

his head, the artist suddenly swung it down, shattering it on a tabletop.[13]

In September of the same year, a Fluxus gang in Wiesbaden performed Corner’s Piano

Activities. A photo shows Maciunas, Higgins,

Vostell, Patterson and Williams cutting into a grand piano with a tree saw. Crowbars

and hammers were also inflicted on the hapless instrument. In the following

year, at Paik’s Exposition of Music Electronic Television in Wuppertal, three prepared pianos and thirteen

prepared television sets were demolished. At the opening, Beuys took an axe to

one of the pianos.[14]

Such demolitionist tendencies

are by no means limited to music, or the overlapping of music, performance and

visual art in Fluxus. We could trace a certain family resemblance across all of

the arts in the wake of World War II. Two streams or tendencies are entwined,

converging and diverging with a pulsing ambivalence: one, more cautious,

forsakes or abandons traditional object-making and makes a leap into

performativity, which then becomes a new object of investigation; the other,

less restrained, attacks traditional culture, at first symbolically but soon

enough literally. Both streams are globalized.[15] The Lettristes in Paris

liquidate first poetry and then cinema. Fontana stabs and slashes the canvas in

Milan, while in Japan, Shozo Shimamoto punches and kicks through stretchered

paper and Kazuo Shiraga wrestles mud. Neo-Dada here and there cries havoc and

raises hell. And so on. Nouveaux Réalistes Daniel Spoerri and Arman carried the

demolition into sculpture. In 1961, Spoerri made two works of papable menace: Hommage

à Fontana, which carries the

painter’s slashes into an image of actual throat-cutting, and Les lunettes

noires, a blinding booby-trap that

jokes grimly on the optimist’s rose-colored glasses, even as it raises the

stakes of Man Ray’s Gift.[16]

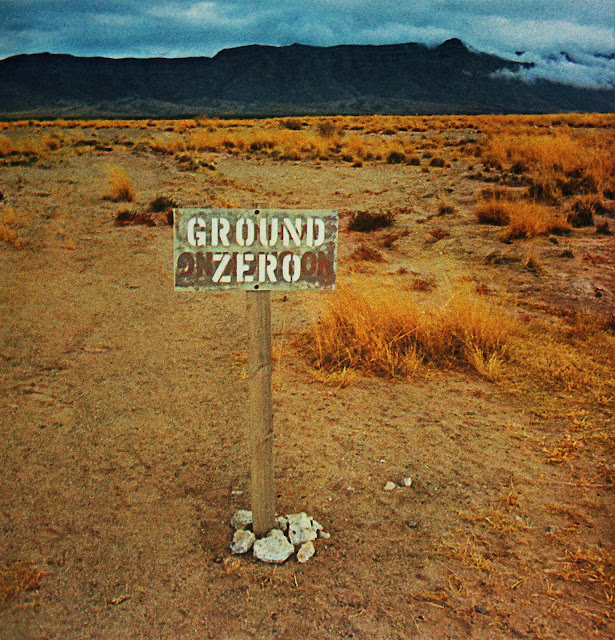

Also in 1961, the year before Paik destroyed a violin onstage, Arman began his colères (tantrums or rages), in which beautiful stringed

instruments of traditional music were systematically smashed to pieces,

more or less instrument by instrument – a violin, a bass, a mandolin, a piano, a harp – and

the gathered bits and splinters affixed to boards. Three years later, in 1964,

he varied the gesture in the combustions series; this time he burned the instruments to crisps and hung the

charred remains on the gallery walls. This cursory highlighting would of course

need to be backed up by close readings of specific works in context. But it

suffices to indicate how far such attacks on the media and body of art can be

grasped in general as mirroring displacements of the violence and trauma of the

war.

‘This radically guilty and

shabby culture’ (Adorno)

The bulk of postwar art

was undoubtedly restorative and accommodating. But even if it is granted that

the examples I have cited do constitute countertendencies of hostility and a

crisis of faith in art’s traditional authority, why should we think they are

responses to World War II? The period indicated, from 1945 to the mid-1960s, is

after all complexly full of momentous transformations, antagonisms and

struggles. What about the Cold War and nuclear arms race, whose shadows fell

constantly on the economic miracles of reconstruction culture? What about the

anti-colonial struggles and wars of national liberation flaring across the

so-called Third World? Was there not always much to be worried, anxious and

angry about? Was not the traumatic ferocity of the Algerian War, for example,

the more potent context of Nouveau Réalisme? Such questions are valid and point

to factors that were no doubt operative, but the tumults and stresses of the

postwar period unfolded within a global social process that was itself radically

and irreparably altered by the violence of World War II. It is Adorno who

announces and clarifies this.

Auschwitz, for Adorno, is not, strictly speaking, the catastrophe. The

catastrophe is rather the global social process founded in and reproduced by

antagonism and violence. All societies structured around the division of manual

and intellectual labor and the domination of man and nature are doomed to ‘perennial

suffering’.[17] Capitalist modernity is the latest and most totalizing form of

such a class society. Nor did Soviet-style ‘actually existing socialism’ offer

any liberating alternative. In both ‘late capitalism’ and its stunted rivals in

‘the East’, Adorno saw the same two dominant tendencies unfolding:

‘integration’, or the tightening of social control and increasing elimination

of difference under the reign of identity-thinking, and ‘administration’, or

the expanding powers of bureaucratic concentration and managerial direction. In

a globalizing society of expansive states and corporations tending toward

‘total administration’ and ‘total integration’, the scope for autonomous

subjectivity, capable of spontaneous experience and feeling as well as a

practice of critical thought, is progressively restricted. Dominated

individuals are trained to accommodate themselves to social and economic forces

indifferent to their happiness and beyond their control. Their anxiety and

repressed rage over this apparent fate predispose them to fascistic appeals and

ensure that episodic genocidal eruptions will be a perennial feature of

contemporary life.[18] In this light, Auschwitz was only the ‘first test piece’

(erstes Probestücke), the proof

that the tendencies of integration and administration contain within them the

logic of genocide: ‘Genocide is the absolute integration.’[19]

The industrial murder of

whole categories of individuals, then, was a latent potential within capitalist

modernity that was actualized under the specific conditions of Nazism and war.

Racism and anti-Semitism were unquestionably central to the conception and

execution of the Nazi genocide. However, the essence of Auschwitz, the fully

globalized meaning and implication of this actualized potential, cannot be

located in or reduced to anti-Semitism.[20] Once demonstrated, this potential

haunts all forms of contemporary society, as a deployable power of state

terror. Auschwitz was a qualitative leap in violence that reaches into and

changes – must change – the very meaning of life, humanity, society, the

future. Nor was it the only such leap, in the context of World War II.

Hiroshima, the other threshold-crossing event of violence, demonstrates a

different potential: the terminally genocidal power of weapons systems produced

under the merger of science and war machine. Adorno takes note of Hiroshima in

numerous places, but does not develop

its implications in a way comparable to his meditations on Auschwitz.[20]

Nevertheless, it follows relentlessly and necessarily from his arguments that

Auschwitz and Hiroshima must be thought together, as historically-demonstrated

genocidal potentials that remain entangled in the tendencies of the

contemporary social process.[21] The meaning of the change that this imposes on

us all, without exception, is that the future of humanity, in any form at all,

is now in question and fully open to doubt. We may not survive our own social

process.[22] Auschwitz and Hiroshima are the end of the myth of automatic

progress, full stop. ‘No universal history leads from savagery to humanity, but

one does lead from the slingshot to the megaton bomb.’[23] For Adorno, then,

the catastrophe is emphatically not in the past, an event that happened once

and now is to be avoided. We are in the catastrophe and it is ongoing.

The implications of this

for art, Adorno argued, are intimidating. With modernity, the arts had acquired

a new autonomy, claiming their place, along with letters, learning and

autonomous science, within an honored production of ‘spirit’ (Geist). But such ‘culture’ remains the luxury of an

extracted social surplus, conditioned on the division of manual and

intellectual labor and thus implicated in domination. Emphatically

differentiating itself from ‘life’, art nevertheless remains bound to it. As

flaring promise of happiness, art cannot become the praxis that would realize

what is promised. And this constitutive frustration converts art’s very refusal

of function into functioning affirmation of the given social reality. Art’s ‘double-character

as both autonomous and fait social’

is thus an antagonism that ‘announces itself unceasingly from the zone of its

autonomy’.[24] And the same antagonism haunts all autonomous culture

conditioned on the splitting off of spirit in the division of labor, tainting

its claim to enlightenment: ‘all culture shares society’s nexus of guilt’.[25]

As the social process of modernity unfolds, and its totalizing tendencies of

integration and administration undermine the very autonomous subjectivity on

which culture depends and for which it alone can have any redeeming meaning,

art’s predicament becomes increasingly acute. Under the heading of ‘culture

industry’, Adorno and Max Horkheimer describe how the market, mediating these

social pressures, tends systematically to undermine art’s autonomy and, behind

the mirage of diversity, to reduce culture to conformist ‘Ähnlichkeit’ (sameness).[26] Even before Auschwitz, a crisis

of faith would merely have reflected an accurate registration of social

reality. After it, art’s ‘very right to exist’ is in question, as the opening

sentence of Ästhetische Theorie

announces.[27]

These critical reflections

and arguments, developing and deepening in the period from Dialektik der

Aufklärung (1944) to Adorno’s

death in 1969, are the context in which we have to read his assertion that ‘after

Auschwitz, to write a poem is barbaric’ – and indeed has become ‘impossible’ (unmöglich).[28] Written in 1949 and first published in 1951,

at the end of the programmatic essay ‘Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft’, this

infamous provocation only began to circulate widely in 1955, as the lead essay

of Prismen. Adorno would

subsequently revisit this claim, moderating and qualifying it, but pointedly

leaving it in force.[29] If, as we have seen, the social process in general is

tending to restrict and eliminate the very conditions of autonomous

subjectivity, then the subject of spontaneous experience and feeling who could

write or read lyric poetry is disappearing with it. And if Auschwitz is the

demonstration that this tendency carries within it a genocidal potential, then

the meaning of Adorno’s provocation emerges clearly: poetry, already becoming ‘impossible’

through the loss of autonomous subjects who are its necessary condition, now

becomes barbaric, if, failing to register the social catastrophe, it attempts

to carry on as if nothing has happened. This first formulation, then, is a

demand for self-reflectivity, a wake-up call that challenges art to attain full

awareness of its own plight.[30]

Summing up in Negative

Dialektik, Adorno insists that

Auschwitz is the unanswerable proof of ‘culture’s failure’ (das misslingen

der Kultur):

‘After Auschwitz, all culture,

along with the urgent critique of it, is garbage. In restoring itself after

what took place in its own landscape, it has become entirely the ideology it

was potentially, ever since it presumed, in opposition to material existence,

to inspire that existence with the light that the separation of spirit from

bodily labor withholds from it. Whoever pleads for the preservation of this

radically guilty and shabby culture makes himself its accomplice, while whoever

refuses to have anything more to do with culture directly promotes the

barbarism that culture revealed itself to be. Not even silence gets out of the

circle.’[31]

Art and the whole

tradition of enlightened culture, then, must bear the ordeal of this

predicament, reflecting on its own failure, origins and continuing dependence

on injustice, brought to a head by its impotence in preventing or resisting genocide.

It can neither permit any uncritical restoration of its ostensible authority,

nor flee the field before the tightening knots of a hostile and totalizing

system.

Adorno’s critique of

traditional culture helps us to understand the gestural violence of the artists

and works I have cited. Struggling to find their way to the clarity eventually

expressed in Adorno’s late texts, these artists at first more or less blindly

‘acted out’ the predicament Adorno specifies.[32] Later on, we will see, some

of them were able to work it through to moments of lucidity. The demolitionism

that some artists directed toward art is misplaced, but is at least

understandable. Moreover, we note that Adorno’s first formulations of the

‘after Auschwitz’ problematic set out a general, structural predicament that

argues from the tendencies of a global social process and an analysis of art’s

position within that process. It is not yet a question of representing the

catastrophe in art.

Endgames

In the 1962 radio talk and

essay ‘Engagement’, in the context of a running polemic against committed art,

Adorno begins to grapple with the issue of artistic representation.[33]

Considering the various strategies by which artists have tried to represent

Auschwitz and the larger social catastrophe to which it belongs, Adorno begins

to theorize and advocate for a form of dissonant and hermetic production

grounded in negative presentation. Adorno concludes that Brecht’s and Sartre’s

committed representations are too direct, distorting and trivializing. As he

later summarizes this critique in Ästhetische Theorie: ‘Artworks exert a practical effect, if they do so

at all, through a barely apprehensible transformation of consciousness, and not

by haranguing.’[34] Kafka, Schoenberg and, above all, Beckett become his

favored models.

The new elaborations of a

negative art of dissonance, I have argued at length elsewhere, are Adorno’s rewriting

of the traditional sublime – or, more precisely, his attempt to understand how

Auschwitz has made the old sublime impossible and replaced it with something

radically different.[35] The traditional sublime had marked a passage from

terror and disturbance to a pleasing self-admiration. The imagination’s

distress before the power or size of nature was rescued by reason, which

reminds the subject of its supersensible destiny, as a free moral agent. But

after Auschwitz and the dead letter of automatic progress, the saving recourse

to human dignity is foreclosed. The terror of the social process supplants that

of nature as the trigger of the sublime, but now the terror remains in force.

Indeed, autonomous reason, if that can be found at all, now confirms precisely

this. In the negative art Adorno favors, any feeling of enjoyment, any pleasure

still generated by the mimetic structure of artistic semblance, is pulled back

into terror when scrutinized. The subjects of this sublime are damaged, remnant

subjects; they can only watch, as from barrels in the maelstrom, their own slow

orbiting descent around the sucking trauma of history. The forceful dissonance

of unreconciled artworks, Adorno argues, triggers the emphatic ‘anxiety (Angst) that existentialism only talks about’.[36] In Ästhetische

Theorie, he will call this effect ‘Erschütterung’ – ‘shudder’.[37]

Kant had introduced the

notion of ‘negative Darstellung’

(negative presentation) in connection with the sublime in the Kritik der

Urteilskraft (1790). In a passage

famously including an admiration of the image ban of Jewish Law, he notes that

abstract notions, such as the ideas of infinity or God, can be represented

negatively, and that the feeling of the sublime loses nothing by a negative

approach.[38] Similarly, Adorno argues, the ‘abstractness of the objective law

prevailing in society’ cannot be captured in positive pictures or the

simplifying fables of committed art.[39] Like the God of old, the social catastrophe

can only be evoked and avowed negatively in art. Even Schoenberg, Adorno

implies, does not always remember this. Criticizing The Survivor of Warsaw, Adorno suggests that it is still too positive. The

remnants of enjoyment that still cling to even the most ascetic and rigorous

artworks, as the structural effect of semblance as such, have to be resisted.

Such remnants threaten to turn art ‘about’ Auschwitz into a new violation of

the victims. Only the most indirect, coded and hermetic representations of the

victims’ suffering generate adequate resistance and counter the enjoyment

intrinsic to art. For Adorno, Beckett shows the way. He evokes the catastrophe

in its essence, not by direct invocation or committed haranguing, but by

showing just how little is left of the autonomous subject in its crisis. In Endgame, the catastrophe comes onstage as the news that

Hamm has run out of painkiller.[40] ‘Beckett responds to the situation of the

concentration camp in the only way fitting – a situation he does not name, as

if it were subject to a Bilderverbot. What is, is like the concentration camp.’[41] Or again, from

Adorno’s 1961 essay on Endgame:

‘Only in silence is the name of the catastrophe to be spoken.’[42]

Adorno took a long time in

coming to a position on the poetry of Paul Celan. For his part, the poet

wrestled courageously with Adorno’s challenge. Celan’s Engführung, his radical 1958 reworking of Todesfuge (1945), was written in a full awareness of Adorno’s

works and arguments.[43] At the end, in the unfinished Ästhetische Theorie, Adorno granted Celan a place on his small list of

those deemed to have successfully responded to the plight of art after Auschwitz.

Arguably, this is the closest Adorno ever came to a real retraction of his 1951

stricture: ‘In the work of the most important contemporary representative of

German hermetic poetry, Paul Celan, the experiential content of the hermetic

was inverted. His poetry is permeated by the shame of art in the face of

suffering that escapes both experience and sublimation. Celan’s poems want to

speak of the most extreme horror through silence.’[44]

Negative Evocation and

Avowal in the Visual Arts

In the visual arts,

negative presentation had to develop in a different way. Found objects are

fully positive presentations, rather than mimetic representations, of selected

fragments of empirical life. But we have already seen that found objects can

also function as negative presentations of other things that are withheld: the

piano and staff board in Plight

are direct and positive

presentations of these objects but are negative presentations of music. The negative evocation

works because the association of these objects with music is established and

instantaneous. This suggests that negative presentation depends, and perhaps

always depends, on a positive image or association that stands behind or

underwrites it.

Before it would be

possible to attempt a negative visual presentation of Auschwitz, for example,

it would be necessary for positive images to circulate widely, deeply and long

enough to become burned into public consciousness – and presumably to do so

against strong resistances and tendencies toward forgetting, avoidance and

disavowal. Their establishment in public awareness would not at all suffice to

demonstrate that either the Nazi genocide or the catastrophe in Adorno’s larger

sense had actually been worked through and processed; it would indicate only that

the minimal awareness necessary for critical processing was at least in place.

Once the positive images are so established, however, once it can be taken for

granted that most people have been exposed to and carry the trace of such

images, then it is possible to work with them without showing them. The release

of Resnais’ Nuit et brouillard in

1955 was the vehicle of this dissemination and, as such, had a profound impact

not just on public consciousness, but on European artists. It seems in fact to

have opened and stimulated the investigation of negative presentation, as a specifically

visual strategy for evoking and avowing traumatic history. The film’s form itself, alternating and

contrasting archival still and moving images with newly shot color footage of camp

ruins in pastoral landscapes, poses the problem of representation, which

Cayrol’s text then articulates explicitly at several points. If Claude

Lanzmann’s 1985 film Shoa is

now recognized as a landmark of negative presentation in film, his ‘fiction of the

real’ probably depends, more than Lanzmann would care to admit, on the impact

of Resnais’ earlier documentary. Lanzmann criticized Resnais’ film for showing

too much, too positively, while the actual genocide of millions, taking place

in gas chambers, are terror scenes of which no film exists and to which no

image could be adequate.[45] Without denying the truth of this, the force of

Lanzmann’s combination of rigorous refusal of documentary images and a

devastating accumulation of testimony is only intensified by our past exposure

to positive images. Indeed, this exposure is necessary if we are to grasp,

through Lanzmann’s work, how inadequate such images must be.

After just a few years, in

which implications of Resnais’ film were evidently absorbed and translated into

an agenda for further research, the investigation of negative presentation as a

means for the visual avowal of traumatic history began in earnest in Paris,

where Nuit et brouillard received

its primary reception. From 1959 on, the dots were connected very quickly

within the group of Nouveaux Réalistes. Issues that previously were of artistic

interest only as problems of form, such as the relation between performance and

trace in mark-making, were revisted under the pressure of a growing awareness

of catastrophic history and its grounding in an ongoing social process. When

Yves Klein returned to figurative painting with his anthropemétries in 1960, he would recover ground

already explored by Robert Rauschenberg, for example in his negative figures

made with floodlit blueprint paper in 1949. But Klein had now seen the shadows

burned onto walls and sidewalks of Hiroshima during the atomic bombing. In

1961, the year after France exploded its own atomic bomb and Resnais’ and

Marguerite Duras’ feature film Hiroshima mon amour opened in cinemas, Klein’s anthropométries made a sharp topical veer toward the real: in the

sequence from People Beginning to Fly to Hiroshima, a

potential of negative presentation has become lucid. History forces the

dialectic of form and content, and figuration after 1945 cannot be what it was

before.

More pertinent here were

the sculptural investigations of Spoerri and Arman. In his tableaux pièges (snare pictures), begun in 1960, Spoerri fixed the

objects found on everyday tabletops, shifted them in situ onto the vertical

plane and hung the result on the wall. In their negative reconstruction of specific

scenes of conviviality and contingency, his pièges

of meals and shared tables in effect turn the trace into historical evidence,

and the assemblage of found objects into forensic exhibit. In 1959,

Arman made his first poubelles

(rubbish bins), boxes and vitrines filled with found garbage and refuse, as

well as his first accumulations,

serial collections of specimens of the same or similar object. As Benjamin

Buchloh’s analysis of these works and their context establishes, Arman’s

cumulative reflections of commodity culture and its garbage transform the

tradition of found object and readymade and announce ‘the end of the utopian

object aesthetic’.[46] Quite clearly, the hope and optimism that Duchamp and

other artists from the early avant-gardes had sometimes invested in

industrialized objects have been objectively liquidated along with the myth of

automatic progress. Readymades are no longer optimistic exactly to the degree

that optimism in general is no longer possible, and this is an objective

problem, as Adorno made clear, that is not alleviated at all by the

reconstructed pseudo-optimism of commodified abundance. With eloquent

precision, Spoerri’s Lunettes noires make the same point.

I am less convinced that

Arman’s selection and manipulation of found objects under postwar conditions empty

these objects of every kind of charge and aura, as Buchloh’s account in places also

suggests. If we supplement his account by tracing the thread of negative

presentation, as I do here, then the story becomes more complex. Arman’s portraits-robot registered the fact that the invisible charge

connecting individuals to their things exceeds and survives a mere relation of

possession. Individuals can be evoked negatively in a very precise way by the

presentation of things that are linked to them, and Arman shows this in those

‘portraits’ of his dealer and friends that seem merely to sample each one’s garbage.

These jokes in poor taste also look to the stage properties of Beckett’s Fin

de partie, which premiered in

London in April 1957 and was playing in Paris three weeks later: in that dismal

work, Hamm keeps his elderly parents, Nagg and Nell, in two dust bins.[47] Yet,

even the exhibited misery and obsolescence of a subjectivity facing its

historical endgame carries a certain pathos that we, the crippled remnants of

subjectivity still clinging to damaged life, are able to feel and register.

Similarly, as we have seen with the colères and combustions of musical instruments, the destruction of these

very auratic objects, with their fragile wooden bodies and warm patinas,

produces a secondary aura: the flaring halo of a traditional culture that, like

the subject, is in the process of disappearing – and only dimly grasps the objective

ground for its demise. For sheer, shocking antihumanism, the smashing or

burning of violins and pianos is on a par with the burning of books; even as

artistic gestures, all these acts implicitly threaten the body itself with

violence. It is wrong to assume or conclude that there is no pathos at all

generated by culture’s crisis, even if the operative feelings fluctuate

unstably between terror, rage, dismay and shame. It is not a matter of no aura

at all, then, so much as a need to specify exactly what kind of auratic charge

is structured, if even as potential, in Arman’s objects.[48] In this direction,

we must be painfully precise.

It is now established, and

known by those who have taken the trouble to inform themselves, that Auschwitz

and the other Nazi murder factories were the scene of a theft so immense and

systematic that it recalls Marx’s famous account of violent, ‘so-called

original accumulation’ (sogenannte ursprüngliche Akkumulation). At these camps, the victims were not just killed;

their bodies and personal property were plundered without restraint, in ways so

gruesome and appalling that it defies belief. At Auschwitz, where alone a

million victims were murdered, ninety-percent of them Jews, the stolen property

was carefully sorted and stored in special warehouses, sardonically called

‘Canada’ by the prisoners forced to carry out this criminal labor. When the

Nazis evacuated Auschwitz before the advancing Soviet army in January 1945,

they blew up the crematoria and attempted to burn or destroy all obvious

evidence of the genocide. But much evidence still remained, and Soviet

cameramen on scene at the camp’s liberation recorded immense pyramids of sorted

clothes, suitcases, eyeglasses, shaving brushes, everything of any possible

value to the Nazi war economy – even dentures stolen from corpses as the teeth

of victims were ransacked for gold caps and fillings. Nearly an hour of

archival film footage exists, and excerpts were shown as evidence at the War

Crimes Trials in Nuremburg. Excerpts were also utilized for some of the

montages of Nuit et brouillard,

which shows stolen eyeglasses, bowls and clothing. Stills taken from the reels

of moving image may have had a wider circulation that remains unmapped.

Two of Arman’s works in

particular are exact reconstructions, on a much smaller scale, of these

documentary images. La Vie à pleines dents, from 1960, is

a disturbing accumulation of dentures; and Argus extra myope, from 1961, gathers and boxes found spectacles. Both

are negative presentations of the individuals, whose personal belonging these

dentures and eyeglasses actually were. At the same time, by reason of a visual

linkage to history that is far too precise to be dismissed, these works evoke

other people whose dentures and eyeglasses were stolen in the course of their

administered murder. By this second evocation, these works of Arman avow the

Nazi genocide. The artistic potential uncovered and mobilized here, then, is

very clear. This is how visual negative presentation works and how it

‘remembers’: these works avow –

they assert that these evoked people existed but were murdered, and that this

crime was perpetrated. And this avowal is indeed charged with an awful aura.

Buchloh notes these echoes

of Nuit et brouillard and

concludes: ‘In their extreme forms, Arman’s accumulations and poubelles cross the threshold to become memory images of the first historical

instances of industrialized death.’[49] But he hesitates to assign any

interpretive primacy to this avowal or to explore the implications further. The

‘inevitably limitless choice of Arman’s object aesthetic’ points Buchloh rather

to the new conditions for subject formation – the enforced identification with

‘sign exchange value’.[50] Taking all of Arman’s production into account, these

two works and perhaps a handful of others that articulate a similarly precise

avowal do seem to be overwhelmed by the sheer volume and randomness of the

artist’s accumulations. This far, Buchloh’s point must be taken. Yet, it must

also be said that the relation of these few works to Arman’s total output also,

and crucially, mirrors and avows the position of industrial murder within the

general, global logic of capitalist accumulation: it is there, actually, before

our eyes, visible but not necessarily seen – a poorly understood potential or

latency that we may well miss in the flux and flood of commodified life and

spectacular culture. Buchloh’s claim, that a ‘dialectic of silence and

exposure’ (or ‘of disavowal and spectularization’) forms the historical

framework of postwar art, is unquestionably correct.[51] But in Arman’s case, we

can see that it is by negative presentation that his work is able to avow the

full catastrophe, in Adorno’s sense.

It is necessary at this

point to insist that this efficacy of negative presentation does not depend on

artistic intention. These visual linkages to history are irrefutably objective.

Coded into these works are potentials for precise evocation and avowal that, as

soon as they are activated, produce effects – including the hit Adorno called ‘shudder’.[52]

This holds true even if these linkages were produced unconsciously – even if

Arman was utterly blind to what he had done. Nevertheless, a few other works by

this artist indicate that he in fact was quite lucid about it. Tuez-les

tous, Dieu reconnaître les Siens,

from 1961, is an accumulation of household insecticide pumps. The prominent

brand-names of some – Fly-Tox, Flit, Projex – testify to the commodification

even of poison. Here we have to remember Clov, in Beckett’s Fin de partie, who, discovering a flea has gotten inside his

pants, doses his own genitals with poison. As Adorno noted, the scene is one of

several in this work that point to the endgame of human domination of nature,

which was always self-repressive and carried latently within it a reversal of

the instinct for survival. Moreover, insecticide is historically entangled in

the pre-history of Zyklon-B, the toxin used in the Nazi gas chambers: ‘Insecticide,

which pointed toward the death camps from the very beginning, becomes the

end-product of the domination of nature, which now abolishes itself.’[53]

Arman’s title is a line imputed to the Abbot of Cîteaux, the Church official who

commanded the massacre of the inhabitants of Béziers, in the south of France,

in 1209, during the Albigensian Crusade. It expresses the moment in the

escalation of administered violence when the jump is made to whole categories

of people, all the members of which are to be targeted and killed

indiscriminately. After Auschwitz, racializing translations of the slogan

continue to circulate; one in English (‘Kill them all and let God sort ’em out’)

seems to have been popular among US soldiers in Vietnam and, passing through

the proxy wars of the South African apartheid regime a decade or so later, to

have become a badge of mercenary culture.[54] To point quickly in passing to

two more accumulations: Le village des damnés, from 1962, packs dolls of children into a glass

vitrine as tightly as those deported to the camps were packed into cattle cars;

Birth control, from 1963,

echoes this, but this time the dolls are packed in a hinged cardboard box that

evokes the suitcases of the deported.

One more aspect of the

Nazi genocide must be attested before this constellation of references can

throw its negative light on Plight.

The makers of Nuit et brouillard

produced a German-language version, with Paul Celan’s translation of Cayrol’s

text. Nacht und Nebel opened in

German cinemas in late 1956, and in April 1957 was broadcast on German

television.[55] In the sequences treating the Nazi plunder of victims, Resnais’

film takes note of the fact that the victims’ hair was shaven, collected in

depots, and eventually turned into ‘cloth’ or textile (tissu). Several images show a pyramid of human hair, and

another shows what is presumably raw human hair, in a column-like form wrapped in

paper. The paper is marked: K[onzentrations].L[ager]. Au[schwitz] Kg 22. The

voice-over for this sequence tells us ‘Rien que des cheveux de femme… A

quinze pfennigs le kilo…On en fait du tissu.’ (Nothing but women’s hair… at fifteen pfennigs a kilo… it’s used to

make textile). What the hair was turned into, actually, was felt. At Auschwitz,

Soviet cameramen filmed the seven tons of human hair that was packed for

shipment to German factories, where, other captured documents entered into the

record at Nuremburg revealed, the hair of the victims was routinely turned into

felt. In these sequences, which last more than a minute, we see 293 column-like

sacks of hair, laid on their sides in two stacks, end to end. The sacks are

roughly the size of the 284 felt columns used by Beuys to line the walls of Plight. The Soviet film footage was reissued in 1985, for

the fortieth anniversary of the war’s end. In the same year, Lanzmann released Shoa and Beuys opened Plight in London.[56] In the Pompidou catalog, the full

title of Beuys’ work, which presumably reflects the artist’s retrospective

alteration of the dating, is: Plight 1956-1985.

The Avowal of Plight

We now have all we need to

understand what this work is and how it does what it does. Beuys took a long

time to attain this synthesis, which in its quiet, restrained precision and

power is unequalled by anything else in his output. In the interval before: the

Eichmann Trial (1961-2), the Frankfurt Auschwitz Trials (1963-5), the German

student movement and global uprisings of 1968, the trauma of the RAF. And

several decades of playing the art game: haranguing from chalkboards, melting

fat, wearing felt, wrapping pianos with it. By 1985, he was ready, whether or

not he had full and lucid consciousness of what he pulled together there. In constructing

a sculptural afterimage to enclose this space, Beuys in effect ‘snared’ the

sacks in the hair room at Auschwitz and flipped them up from the horizontal to

the vertical, just as Spoerri did with his pièges. In standing ranks, the felt columns now evoke the

victims by negative presentation – this time through the inescapable

specificity of an irrefutable material linkage. The thermometer, we can now

see, evokes the crematoria and lies on the staff board and piano like a

crushing weight or pressure that holds it closed and keeps it silent.

We now have an avowal of

the catastrophe that, at the same time, allegorizes art’s predicament after

Auschwitz, just as Adorno theorizes it. Music, the medium of raw feeling and

deep consolation, will not be adequate before the facts of what happened; art

will have to shut up. Or rather, because not even silence gets us out of the

circle, art will have to go on, bearing its shame and the challenge to break

radically with its affirmative tradition. Only in silence can the name of the

catastrophe be spoken, but still it must be spoken – if only through the

dissonance of a negative, hermetic installation. This one, here, now, puts the

spectator under the surveillance of a community of evoked victims, ranked along

the walls, as if along fences of barbed wire. The title confirms the

interpretation and takes its place within it: if the avowed trauma was that

than which no worse can be conceived, it remains, in its urgent legacy for us,

a situation of extreme danger and difficulty. Even the secondary meaning of

‘plight’ piles on, as a question that, given the tendencies of the social

process, we must leave open: the situation imposes on us a duty and promise, but

only insofar as we can still claim at all to be autonomous, ethical, political

subjects. Maybe, in the trial and moment of truth, we earn that designation,

maybe we do not. In this work, there is no trace of confident posturing,

jester’s tricks, or the weird dancing of shamans. The work draws no conclusions

about our capacity either to fathom the horror or save ourselves from it. It

simply avows: that happened and

so it is. The disturbance of this work – attested by the punches and kicks of

spectators, imprinted into the columns of the second room – leads through the

dead-end, to the shudder of the after-Auschwitz sublime.

To have said this is not

to have said everything. One would like to say more, and should. Avowal is a

moment only – of and in a social process that churns on in defiance of all

avowals. What we do with our avowals, where we go with them and how we put them

to work, with others, is another, more political matter. The sublime, in

itself, is not self-rescue, any more than it ever was. We may think Plight, as synthesis and culmination, came rather late in

the dialectic of avowal and avoidance. But the irony, if that is what we must

call it, lies elsewhere: in Plight’s

reception, which long managed to avoid what the work avows, and in the social factum

brutum that all the accelerated

proliferation of remembrance in art and official culture since has not resulted

in any global public lucidity about the social process. Its powers of terror,

far from being arrested, have only continued to grow. Rememoration is not

always, not automatically, counter-memory. It is no longer 1985.

This essay is forthcoming in 2014 in Nordic Journal of Aesthetics; a German translation will appear in 2013 in Beuys-Brock-Vostell:

Three Positions of Performativity, eds. Wilfried Dörstel, Eckardt Gillen,

Franz van der Grinten, and Peter Weibel, in association with the exhibition of

the same name at ZKM/Museum of Contemporary Art in Karlsruhe.

Notes:

[1] Dissemination is a

process rather than a sudden event of universal transmission achieved with

perfect success, once and for all, upon first exhibition or publication.

[2] See my 'Joseph Beuys

and the After-Auschwitz Sublime' in Gene Ray, ed., Joseph Beuys: Mapping the

Legacy (New York: D.A.P. and The

John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, 2001), pp. 59-61; and revised in Ray, Terror

and the Sublime in Art and Critical Theory (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), pp. 37-8.

[3] The London configuration is

the main focus here. I do not take into account later alterations, such as clear plexiglass barriers lining the entrance passageway, introduced into the Paris version at the Centre Georges Pompidou, or damage inflicted by spectators.

[4] As far as I am aware,

Beuys is not suspected of any direct participation in the Nazi genocide. How

much he may have known about it, from within the Nazi war machine, is less

clear and more open to controversy, but in the absence of irrefutable evidence

remains unknowable.

[5] John Cage, Silence (Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press, 1973),

pp. 13-4.

[6] Ibid., p. 17.

[7] Ibid., p. 47.

[8] Cage’s name appears

only once, in passing, in Adorno’s Ästhetische Theorie, but there Adorno aligns him with Beckett’s

reduction of meaning to the absence of any redeeming meaning: ‘Schlüsselphänomene

mögen auch gewisse musikalische Gebilde wie das Klavierkonzert von Cage sein,

die als Gesetz unerbittliche Zufälligkeit sich auferlegen und dadurch etwas wie

Sinn: den Ausdruck von Entsetzen empfangen.’ (‘Key phenomena may include

musical constructions, such as the piano concert of Cage, which by imposing relentless

chance on themselves as law thereby attain something like meaning: the

expression of horror.’ Ästhetische Theorie [1970], eds. Gretel Adorno and Rolf Tiedemann

(Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp, 1973), p. 231; Aesthetic Theory, trans. Robert Hullot-Kentor (Minneapolis:

University of Minnesota Press, 1997), p. 154. Here and throughout, English

renderings of Adorno are my modifications of the standard translations.

[10] What a shock it must

have been, for example, when the full extent of the Nazi genocide was revealed,

to have remembered his 1942 work for prepared piano, titled In the Name of

the Holocaust, after Joyce’s pun

from Finnegans Wake (‘In the

name of the Holy Ghost.’). Such an accident might fuel anyone’s reflection on

the relation of culture and chance. But for Cage the sensitive American,

Hiroshima was probably the more traumatic detonation.

[11] In that year,

Cage began studies of Zen with D.T. Suzuki and of Indian philosophy with Gita

Sarabhai.

[12] Born in Korea,

Paik finished a thesis on Schoenberg at the University of Tokyo in 1956.

Afterwards in Europe, he studied with Karlheinz Stockhausen in Cologne before

meeting Cage in Darmstadt in 1958.

[13] Contrast this with

Cage’s most extreme embrace of indeterminacy, 0’0”,

performable by anyone in any manner, composed in the same year.

[14] See Douglas Kahn,

‘The Latest: Fluxus and Music’, in Elizabeth Armstrong and Joan Rothfuss, In

the Spirit of Fluxus (Minneapolis,

MN: Walker Art Center, 1993), pp. 100-121; on Beuys and Fluxus, see Joan

Rothfuss, ‘Joseph Beuys: Echoes in America’, in Ray, ed., Joseph Beuys:

Mapping the Legacy, pp. 37-53.

[15] For other readings of

these tendencies in postwar art history, see Paul Schimmel and Russell

Ferguson, eds., Out of Actions: Between Performance and the Object 1949-1979

(New York: Thames and Hudson,

1998).

[16] Spoerri, like Paul Celan and Isidore Isou a Rumanian Jew displaced by the Nazi terror, is probably the most complex and interesting of the Nouveaux Réalistes. By his own account, he fled with his mother and siblings to Switzerland in 1942, his father,

Isaac Feinstein, having been murdered by the Nazis in 1940. See Spoerri's interview with Freddy De Vree in Daniel Spoerri: Detrompe-l'oeil (Antwerp: Ronny Van de Velde, 2000), no pagination. Cf. Susanne Neuburger, ed., Nouveau Réalisme (Vienna: Museum Moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig, 2005), p. 198; and Anekdotomania: Daniel Spoerri über Daniel Spoerri (Basel: Museum Jean Tinguey Basel and Hatje Cantz Verlag), p. 290.

[17] Adorno, Negative

Dialektik [1966] (Frankfurt/Main:

Suhrkamp, 1975), p. 355: ‘das perennierende Leiden’; Negative Dialectics, trans. E.B. Ashton (New York: Continuum, 1995) p.

362. Cf. the variant, ‘das perennierende Unheil’, in ‘Kulturkritik und

Gesellschaft’ [1951], in Prismen (Frankfurt/Main:

Suhrkamp, 1976), p. 16; ‘Cultural Criticism and Society’, in Prisms, trans. Samuel and Shierry Weber (Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press, 1992), p. 25. Both mark the legacy of misery unfolding from the

division of labor, ‘die tödliche Spaltung der Gesellschaft’, ‘Kulturkritik und

Gesellschaft’, p. 15; ‘the deadly splitting of society’, ‘Cultural Criticism

and Society’, p. 24. Pertinently,

the separation of spirit (Geist)

from manual labor is the necessary condition and primal scene of all autonomous

art and culture.

[18] See Adorno,

‘Was bedeutet: Aufarbeitung der Vergangenheit’ [1959], in Eingriffe: Neun

kritische Modelle (Frankfurt/Main:

Suhrkamp, 1963), p. 139; ‘The Meaning of Working Through the Past’, in Critical

Models: Interventions and Catchwords,

trans. Henry W. Pickford (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998), p. 98.

[19] Adorno, Negative

Dialektik, p. 355: ‘Völkermord ist

die absolute Integration.’ Negative Dialectics, p. 362.

[20] Part of Adorno’s

critical provocation is to insist that, essentially, Auschwitz is an absolute

threat that exceeds its historic specificity. Auschwitz qua appearance-form (Erscheinungsform), to use Adorno’s Hegelian idiom, was driven by

toxic and anti-Semitic fantasies of racial purity that took hold, with official

promotion, in Germany, within a highly specific conjuncture of history.

Auschwitz qua essence (Wesen),

however, is the genocidal potential of social tendencies toward integration and

administration. Behind the murder of Jews by Nazis, the logic of modernity

itself is unfolding.

[21] To clarify this was a

main aim of my Terror and the Sublime in Art and Critical Theory; see in particular chapters one and eleven (of the

revised soft-cover edition), as well as my further elaborations in ‘Hits: From

Trauma and the Sublime to Radical Critique’, Third Text 97, vol. 23, no. 2 (2009): 135-149.

[22] As Adorno puts it,

the ‘threat of total catastrophe’ (‘der… Drohung der totalen Katastrophe’) has become ‘allgegenwärtigen’ – omnipresent, ubiquitous, saturating the

contemporary. Ästhetische Theorie,

p. 362; Aesthetic Theory, pp.

243-4.

[23] Adorno, Negative

Dialektik, p. 324: ‘Keine

Universalgeschichte führt vom Wilden zur Humanität, sehr wohl eine von der

Steinschleuder zur Megabombe.’ Negative Dialectics, p. 320.

[24] Adorno, Ästhetische

Theorie, p. 16: ‘Der

Doppelcharakter der Kunst als autonom und als fait social teilt ohne Unterlaß

der Zone ihrer Autonomie mit sich.’ Aesthetic Theory, p. 5.

[25] Adorno, ‘Cultural

Criticism and Society’, p. 26; ‘Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft’, p. 17: ‘alle

Kultur am Schuldzusammenhang der Gesellschaft teilhat’.

[26] Max Horkheimer and

Adorno, Dialektik der Aufklärung: Philosophische Fragmente [1944] (Frankfurt/Main: Fischer Verlag, 2003), pp.

128-176; Dialectic of Enlightenment: Philosophical Fragments, ed. Gunzelin Schmid Noerr and trans. Edmund

Jephcott (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2002), pp. 94-136.

[27] Adorno, Aesthetic

Theory, p. 1; Ästhetische

Theorie, p. 9: ‘nicht einmal ihr

Existenzrecht’.

[28] Adorno, ‘Cultural

Criticism and Society’, p. 34; ‘Kulturkritik und Gesellschaft’, p. 31: ‘[N]ach

Auschwitz ein Gedicht zu schreiben, ist barbarisch, und das frißt auch die

Erkenntnis an, die ausspricht, warum es unmöglich ward, heute Gedichte zu

schreiben.’

[29] In ‘Engagement’

[1962], in Noten zur Literatur,

pp. 422-3; in English as ‘Commitment’, in Notes to Literature, vol. 2, trans. Shierry Weber Nicholsen (New York:

Columbia University Press, 1992), pp. 87-8; Negative Dialektik [1966], pp. 355-6; Negative Dialectics, p. 362; ‘Ist die Kunst heiter?’ [1967] in Noten

zur Literatur, pp. 603-4; ‘Is Art

Lighthearted?’ in Notes to Literature, vol. 2, p. 251; and ‘Kunst und die Künste’ [1967] in Gesammelte

Schriften, vol. 10.1, p. 454; ‘Art

and the Arts’, trans. Rodney Livingstone, in Can One Live after Auschwitz? A

Philosophical Reader, ed. Rolf

Tiedemann (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2003), p. 387.

[30] Both ‘Gedicht’ and ‘Gedichte’ are to be read here as synecdoche for all the

arts, in the same way that “Auschwitz” stands for the Nazi genocide.

[31] Adorno, Negative

Dialectics, pp. 366-7; Negative

Dialektik, pp. 359-60: ‘Alle

Kultur nach Auschwitz, samt der dringlichen Kritik daran, ist Müll. Indem sie

sich restaurierte nach dem, was in ihrer Landschaft ohne Widerstand sich

zutrug, ist sie gänzlich zu der Ideologie geworden, die sie potentiell war,

seitdem sie, in Opposition zur materiellen Existenz, dieser das Licht

einzuhauchen sich anmaßte, das die Trennung des Geistes von körperlicher Arbeit

ihr vorenthielt. Wer für Erhaltung der radikal schuldigen und schäbigen Kultur

plädiert, macht sich zum Helfershelfer, während, wer der Kultur sich

verweigert, unmittelbar die Barbarei befördert, als welche die Kultur sich

enthüllte. Nicht einmal Schweigen kommt aus dem Zirkel heraus.’ Cf. Adorno’s

gloss on ‘Schuld’ (guilt) in Ästhetische Theorie, pp. 347-8; Aesthetic Theory, pp. 234-5.

[32] I of course am not

claiming these artists were all struggling readers of Adorno. The dissemination

of Adorno’s texts may have played a role, but cannot explain everything. It is

the social process, unfolding as history that bears down on all, which both

Adorno and artists responded to, in whatever ways they could.

[33] Adorno’s case against

Brecht is stimulating, but not without serious problems. I examine these in

‘Dialectical Realism and Radical Commitments: Brecht and Adorno on Representing

Capitalism’, Historical Materialism,

vol. 18, no. 3 (2010): 3-24.

[34] Adorno, Aesthetic

Theory, p. 243; Ästhetische Theorie, p. 360: ‘Praktische Wirkung üben Kunstwerke

allenfalls in einer kaum dingfest zu machenden Veränderung des Bewusstseins

aus, nicht indem sie haranguieren.’

[35] See my Terror

and the Sublime in Art and Critical Theory, chapter one; and my summary discussion in 'Hits: From Trauma and the

Sublime to Radical Critique.'

[36] Adorno, ‘Commitment’,

p. 90; ‘Engagement’, p. 426: ‘Kafkas Prosa, Becketts Stücke oder der wahrhaft

ungeheuerliche Roman Der Namenlose üben eine Wirkung aus, der gegenüber die

offiziell engagierten Dichtungen wie Kinderspiel sich ausnehmen; sie erregen

die Angst, welche der Existentialismus nur beredet. Als Demontagen des Scheins

sprengen sie die Kunst von innen her, welche das proklamierte Engagement von

außen, und darum nur zum Schein, unterjocht. Ihr Unausweichliches nötigt zu

jener Änderung der Verhaltensweise, welche die engagierten Werke bloß

verlangen. Wen einmal Kafkas Räder überfuhren, dem ist der Friede mit der Welt

ebenso verloren wie die Möglichkeit, bei dem Urteil sich zu bescheiden, der

Weltlauf sie schlecht: das bestätigende Moment ist weggeätzt, das der

resignierten Feststellung von der Übermacht des Bösen innewohnt.’

[37] Adorno, Ästhetische

Theorie, p. 364: ‘Erschütterung,

dem üblichen Erlebnisbegriff schroff entgegengesetzt, ist keine partikulare

Befriedigung des Ichs, der Lust nicht ähnlich. Eher ist sie ein Memento der

Liquidation des Ichs, das als erschüttertes der eigenen Beschränktheit und

Endlichkeit innewird.’ Aesthetic Theory, p. 245: ‘Shudder, starkly opposed to the usual concept of

experience, is no particular satisfaction of the ego, is not similar to desire.

Rather, it is a memento of the liquidation of the ego, which, shaken to the

core, becomes aware of its own limitedness and finitude.’ At this point, Adorno’s

rewriting of the sublime intersects with Jacques Lacan’s rewriting of Freud’s

theory of trauma in the 1964 Seminar, published as Les quatre concepts

fondamentaux de la psychanalyse (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1973), pp. 63-75, in

English as The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller and trans. Alan Sheridan

(New York: Norton, 1981), pp. 53-64.

[38] Immanuel Kant, Kritik

der Urteilskraft, Werkausgabe, vol. 10, ed. Wilhelm Weischedel (Frankfurt/Main:

Suhrkamp, 1974), p. 201.

[39] Adorno, ‘Commitment’,

p. 90; ‘Engagement’, p. 425: ‘die Abstraktheit des Gesetzes, das objektiv in

der Gesellschaft waltet.’

[40] Adorno, ‘Trying to

Understand Endgame’, in Notes

to Literature, vol. 1, trans.

Shierry Weber Nicholsen (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), p. 260;

‘Versuch, das Endspiel zu Verstehen’, in Noten zur Literatur, p. 303: ‘es keine Nährpillen mehr gebe’.

[41] Adorno, Negative

Dialectics, p. 380. Negative

Dialektik, p. 373: ‘Beckett hat

auf die Situation des Konzentrationslagers, die er nicht nennt, als läge über

ihr Bilderverbot, so reagiert, wie es allein ansteht. Was ist, sei wie das

Konzentrationslager.’

[42] Adorno, ‘Trying to

Understand Endgame’, p. 249;

‘Versuch, das Endspiel zu Verstehen’, p. 290: ‘Schweigend nur ist der Name des

Unheils auszusprechen.’

[43] See the

correspondence between the two, published with an introduction by Joachim Seng

in Frankfurter Adorno Blätter,

no. 8 (2003).

[44] Adorno, Aesthetic

Theory, p. 322; Ästhetische

Theorie, p. 477: ‘Im bedeutendsten

Repräsentanten hermitischer Dichtung der zeitgenössischen deutschen Lyrik, Paul

Celan, hat der Erfahrungsgehalt des Hermetischen sich umgekehrt. Diese Lyrik

ist durchdrungen von der Scham der Kunst angesichts des wie der Erfahrung so

der Sublimierung sich entziehenden Leids. Celans Gedichte wollen das äußerste

Entsetzen durch Verschweigen sagen.’

[45] See Raye Farr, ‘Some

Reflections on Claude Lanzmann’s Approach to the Examination of the Holocaust’,

in Toby Haggith and Joanna Newman, eds. Holocaust and the Moving Image:

Representations in Film and Television since 1933 (London and New York: Wallflower Press, 2005), pp.

161-167.

[46] Benjamin H. D.

Buchloh, ‘From Yves Klein’s Le Vide

to Arman’s Le Plein’, in

Buchloh, Neo-Avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and

American Art from 1955 to 1975

(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000), p. 270.

[47] This seminal work was

written in French and translated by Beckett into English; a German edition,

however, translated by Elmar Tophoven with Beckett’s approval, appeared even

before the English: Fin de partie

(Les Editions de Minuit, 1957); Endspiel (Suhrkamp, 1957); Endgame

(Grove, 1958). Adorno met and had long discussions with Beckett in Paris in

1958; he had already seen a production of Endspiel in Vienna. The dedication of Adorno’s essay on Endspiel reads, in English: ‘To S.B., in memory of Paris,

Fall 1958.’ On the dustbins, Adorno comments: ‘Beckett’s trashcans are emblems

of the culture reconstructed after Auschwitz.’ ‘Trying to Understand Endgame’, pp. 266-7; ‘Versuch, das Endspiel zu verstehen’,

p. 322: ‘Becketts Mülleimer sind Embleme der nach Auschwitz wiederaufgebauten

Kultur.’ On Adorno’s meetings with Beckett, see Stefan Müller-Doohm, Adorno:

A Biography, trans. Rodney

Livingstone (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2009), pp. 356-60. On the early

production history of Fin de partie,

see Anthony Cronin, Samuel Beckett: The Last Modernist (London: Flamingo, 1997), pp. 458-66.

[48] Walter Benjamin

taught that aura is a charge or effect of distance grounded in various kinds of

authority – that invested in singular artworks, authentic experience or

returning ‘lost time’. We may belong to the era of reproducibility, degraded