|

| Photo: Mandy Barker |

Görg thinks the human

relation to the biosphere is changing in some subtle ways, and he calls for a

nuanced analysis of the domination of nature. As the ecological crises become

increasingly undeniable, he argues, elites are responding in ways that cannot

be characterized as simple denial or disavowal. In the post-Fordist phase of

capitalist accumulation, the historical attempt to achieve utter or complete

mastery of nature is finally understood to be impossible, according to Görg.

Instead, technocrats and CEOs now try to master the unintended negative

consequences of the failing forms of the attempted mastery of nature. But this

‘mastery of secondary effects’ or ‘reflexive domination of nature’ is a

strategy of risk management that does not give up the goal of capital

accumulation. The master logic remains the same, but the degrading biosphere is

now addressed as an assessable risk or ‘security problem’ that must be coped in

order to sustain the expectation of high returns on investment.

|

| Photo: Mandy Barker |

These are helpful

reflections that can illuminate some emerging responses to specific aspects of

the meltdown. They certainly help to understand the oscillations of the ‘green

revolution’ of GMO monoculture, as well as those of its marine twin, the ‘blue

revolution’ of aquaculture. The possibility of profitably feeding the hungry

billions opened the flows the venture capital, and each industry rushed to develop and deploy science- and

technology-fed innovation ahead of its rivals, only to have to cope with devastating unforeseen

consequences, from disappearing pollinators and mutant superweeds to the new viral outbreaks that rage

through the fish and shrimp farms and escape to threaten what's left of wild populations. (On the latter, see Paul Molyneaux’s eye-opening Swimming in

Circles, 2007.) Fix-it-as-we-go

optimism, combining venture capital and techno-hubris, conveniently avoids the

more troubling critiques of method and market.

Görg’s caveats also help

us to throw more light on the social dynamics of plastic accumulation – that

dismal shadow of the contemporary commodity. How did we ever live without it? Between seven and eight percent of

world oil production is used to produce plastics. According to Plastic Oceans Foundation, more plastic was produced in the last ten years than was made in the whole twentieth century. And nearly half is used once and then thrown away. Much of that finds its way to the world's oceans. We are all, in effect, involuntary participants in an experiment that will eventually determine the long-term health effects of exposure to plastics and the ecological effects of its accumulation in the biosphere. Chemicals added

to plastics are known to be absorbed by human and non-human bodies. Some of these are toxic and carcinogenic; others, including bisphenol A (BPAs) and phlhalates, are endocrine disruptors known to interfere with reproductive, developmental and immune systems in humans and wildlife.

When immersed in salt water or fresh water, most plastics leach

hormone disrupting chemicals, and these estrogenic effects are increased

by exposure to sunlight. We are learning to avoid water bottled in

plastic that has been in the sun, but meanwhile on the high seas

drifting continents of plastic have formed simmering soups of toxins. These marine gyres have initiated a lamentable ecocide,

images of which unhappily haunt the biosphere thread of scurvy tunes.

How are we responding to

the plague of plastic? What responses are available to us, as unwilling

consumers? What responses are proposed by the profit-driven producers of it?

What say the technocrats? How are the discourses constructed? Who shapes their forms and appearances? Is there anything

yet that might credibly be called ‘debate' about it?

Recycling and ‘responsible

consumerism’ are of course recommended to us. While such measures are important, any durable solution would have to address the problem where it begins: on the production side, in the

plastics industry, the conventions of commodity marketing and, indeed, the

manufactured fantasies and enjoyments of hyper-consumption. The producers have

understood that ‘secondary consequences’ are emerging problems for them, too,

and that these, as they become more visible and generally understood, are going

to translate into public relations migraines.

The newspaper article

reproduced below appeared last week in the Cyprus Mail. It reports on a campaign co-organized by Waste

Free Oceans, ‘an initiative of the European plastics industry’, and Green Dot

Cyprus, a non-profit company initiated by the Cyprus Chamber of Commerce and

Industry to promote and establish the first collective compliance (recycling)

system in Cyprus. With much fanfare, the campaign has ‘demonstrated’ a trawl

system for collecting marine litter, loaned to Cyprus for a year. The

municipalities are all called on to purchase a trawl and work with local

fishermen, who know best where the plastic is drifting.

Without doubt, this would

be a good and laudable thing. There is much floating garbage in the ports and

near-shore areas that could be captured and collected in this way. When we

visited the sand beaches around Lara, near Akamas, where green and

loggerhead turtles come ashore to nest, there was a shocking accumulation of plastic

flotsam. The language of this campaign, relayed by the report below, gives us

insight into the spectacular logic of ‘reflexive domination’. Detrimental

ecological effects of plastic are now acknowledged. But the accents of the

discourse are on the seen, the visible, the aesthetics of garbage and the

implicit threats these pose to the tourism-dependent economy of Cyprus. Above

all those terrible images of wildlife fatally entangled in plastic bags or

strangled in packaging are to be avoided.

As can be seen, the trawl

system is geared to trap relatively large pieces of floating garbage. But the

ecocidal accumulation of plastic is more invisible and insidious. The large

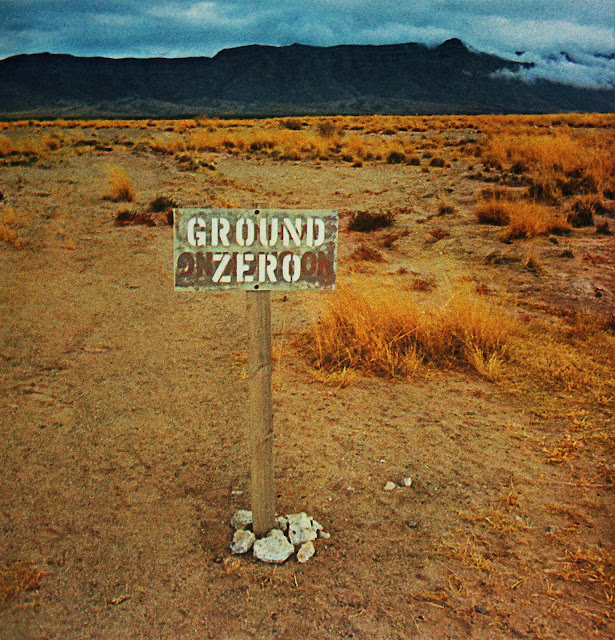

bottles, bags and whatnot eventually break down into crumb-sized fragments. Mandy Barker has collected and re-photographed plastic flotsam in images that

vividly capture the artificial 'life-cycle' and dissemination of plastic. The bits and pieces are mistaken for food by fish, birds, sea turtles and marine

mammals, which slowly starve as the plastic accumulates in their stomachs. In addition to these direct mechanical effects, there are the invisible and still uncertain chemical processes associated with long-term exposure. Gathering up the larger pieces floating

around the coasts will, it is true, prevent those pieces from breaking down and

adding to the gyres of soup. But this is literally a drop in the bucket meant

to protect the aesthetic integrity of the tourist beaches, assuage consumer

consciences and plant the impression that a problem is being effectively

addressed. Such is the greenwashing of plastic.

What is not being said or

proposed? Everything aiming at reducing the amount of plastic produced in the

first place. The measures available range from taxes to outright bans. Industry has long resisted the principle of 'the polluter pays' with the usual threats to move production to more favorable business climates. Plastics producers will moreover claim that they should not be held responsible for litter dumped by consumers. Once health risks and ecological damage are factored in, however, it becomes clear that there are whole categories of plastic products, from bags to bottles, that do more harm than good, even if their 'convenience' has been addictive. Those who have benefited from supplying this dubious demand can certainly be expected and required to direct some profits to mitigating the damage their products do. The plastics industry, the ‘sponsors’ of Waste Free Oceans, should be taxed for producing the problem, and the revenues dedicated to

remediation. The municipalities shouldn’t have to worry about where they will

find funds to buy and operate these trawls, especially in conditions of

enforced austerity. But the ‘voluntary’ corporate initiative on view here is meant

to fend off any such approach.

With regard to ecological sanity in legislation, plastic bags are emerging as a prominent litmus test. The United States uses some 380 billion plastic bags a year. Some nations, including China, Ireland, Australia, South Africa, Taiwan and Bangladesh, have either banned plastic bags outright or levied taxes on their use. Ireland's consumption tax of 37 cents per bag cut usage by 90% in the first year. But the more promising trend is that many municipalities, responding to grassroots pressure, have decided to act in advance of any national initiative. In 2007, San Francisco became the first US city to ban plastic bags in all retail stores, including restaurants. Some 50 more cities in California are now following SF's lead. The unnecessary use of plastic bags became established through their being pressed on us freely at every point of purchase. We consumers, too, should be required to take responsibility for habits we acquired too unthinkingly.

Cyprus, an island in an already troubled Mediterranean, should plan for the long-term and become a leader in adopting ecological accounting. Garbage trawls are nice, but comprehensive obligatory recycling, a ban on especially noxious plastic products and the establishment of a few no-take marine reserves would be far more effective in protecting the integrity of coastal waters and would be a wise investment in the future. If Nicosia is slow to reach these conclusions, municipalities can and should take the initiative. A full assessment of the island's prospects for sustainability would have to take into account all the ecological benefits now taken for granted and all the ecological damage and losses now shifted without calculation onto the backs and bodies of others; these 'externalities' will certainly shape the quality of life in forceful ways. Up for rethinking, in this light, is the long-term wisdom Cyprus' elective dependency on mass tourism.

With regard to ecological sanity in legislation, plastic bags are emerging as a prominent litmus test. The United States uses some 380 billion plastic bags a year. Some nations, including China, Ireland, Australia, South Africa, Taiwan and Bangladesh, have either banned plastic bags outright or levied taxes on their use. Ireland's consumption tax of 37 cents per bag cut usage by 90% in the first year. But the more promising trend is that many municipalities, responding to grassroots pressure, have decided to act in advance of any national initiative. In 2007, San Francisco became the first US city to ban plastic bags in all retail stores, including restaurants. Some 50 more cities in California are now following SF's lead. The unnecessary use of plastic bags became established through their being pressed on us freely at every point of purchase. We consumers, too, should be required to take responsibility for habits we acquired too unthinkingly.

Cyprus, an island in an already troubled Mediterranean, should plan for the long-term and become a leader in adopting ecological accounting. Garbage trawls are nice, but comprehensive obligatory recycling, a ban on especially noxious plastic products and the establishment of a few no-take marine reserves would be far more effective in protecting the integrity of coastal waters and would be a wise investment in the future. If Nicosia is slow to reach these conclusions, municipalities can and should take the initiative. A full assessment of the island's prospects for sustainability would have to take into account all the ecological benefits now taken for granted and all the ecological damage and losses now shifted without calculation onto the backs and bodies of others; these 'externalities' will certainly shape the quality of life in forceful ways. Up for rethinking, in this light, is the long-term wisdom Cyprus' elective dependency on mass tourism.

That said, even to attempt to clean up the five continents of plastic soup

revolving in the world’s oceans would require a serious and cooperative

international effort involving governmental agencies and a substantial redistribution of

public resources. Given what is spent

routinely on national war machines, such a reorienting commitment would be a

possible vector of demilitarization: re-function the navies for a peaceful biospheric mission. But even this kind of utopian reaching

would still be ‘reflexive domination’ aimed at managing ‘secondary

consequences’, rather than the reorganization of desires and production that is

urgently needed. If we don’t change the way we live and produce, we will

continue to add to the soup faster than we could ever vacuum and filter it. But

seeing the problem and its scale more clearly allows the real discussions and

debates to begin. How do we want to live, really, and what other life forms do

we want to have with us in the biosphere? The social process can be changed, when enough of us are ready to accept nothing less. Ultimately, the global majority, thinking and acting where they live, is the only agency capable of this transformation.

GR

For more, see: Mandy Barker, Chris Jordan, Plastic Oceans. A closer review of Critical Ecologies, ed. Andrew Biro, is forthcoming soon.

‘Trawling for Marine

Litter off Limassol’

By Stefanos Evripidou

The Cyprus Mail, October 10, 2012

THE FIRST demonstration of

a trawl system for collecting floating marine litter yesterday took place off

the coast of Limassol, an initiative of the European plastics industry to help

free the seas from debris. Agriculture Minister Sophocles Aletraris welcomed

the official launch of the Waste Free Oceans initiative at the Limassol Port,

noting that: “Marine litter is an environmental, economic, health and aesthetic

problem... (that) can be found everywhere. It has consequences on the marine

and coastal environment and also on human activities.” The launch was organised

by the Waste Free Oceans Foundation and Green Dot Cyprus.

Officials and journalists

were yesterday given a demonstration of how coastal waters can be cleaned up,

with plastic bottles and tins collected using a special trawl which can be

fitted on a normal fishing boat. Green Dot director Kyriacos Parpounas said the

special trawl has been granted to Cyprus for a year. He called on each coastal

town to acquire one over time to ensure Cyprus’ waters are free of floating

debris. “The initiative makes use

of EU fishermen- who know where the floating debris is and move through the

currents of the sea- and the days when they can’t find fish in the sea, they

can use this special equipment to clean the sea from floating debris,” he said.

The aim is to use EU

funding through the Fisheries Fund to permanently support the cleaning of the

seas by professional fishermen in the same way that they are subsidised for

every ton of fish caught, he said. This in turn will help keep the seas clean

while supporting the existence of the fishing profession, said Parpounas. Aletraris highlighted a 2011 UN study,

which found that most of the Mediterranean marine litter, about 80 per cent,

comes from land sources and consists mainly of cigarettes, plastics, aluminium

and glass, while floating marine litter is mainly plastic.

“Therefore, it is crucial

to restrict the problem at its source,” he said noting that millions of

tourists and locals spend a lot of time at the beach in Cyprus. “It is thus,

increasingly important to keep both the bathing waters and the sea coast

clean,” he said.

According to the EU’s

Bathing Water Classification, Cyprus has excellent bathing water quality, while

the main source of pollution identified is the illegal dumping of waste by

ships, said the minister, adding, “More effective measures to control the

illegal discharges from ships are necessary”. Limassol mayor Andreas Christou

said yesterday the initiative comes at a time when the local authority is

considering purchasing a €60,000 boat to clean up the waters around Limassol.

However, the local authority will also take this latest project into consideration

before making a decision, he said.

The Waste Free Oceans

Foundation is an industry-led European-wide initiative to clean up European

coastal waters, set up by European plastics converters. The aim is to provide

solutions to the problem of floating marine debris. Fishing boats outfitted

with a special trawl are able to collect between two to eight tonnes of waste

for cleaning and recycling. According to the foundation’s website, the project

can help reduce the floating marine debris on Europe’s coastlines by 2020 using

fishermen and homegrown technology.

The foundation notes that

many factors have contributed to a rise in marine litter: poor waste management

practices in ports and marinas, dumping by ships and vessels, and the general

public attitudes towards littering. “The implications of an increase in marine

litter are far reaching- affecting both human health and the ecosystem,” said

the foundation.

|

| Photo: Mandy Barker |

|

| Photo: Mandy Barker |

Tremendous issues here. I'm very happy to look your article.

ReplyDeleteThanks a lot and I am having a look ahead to touch you.

Will you please drop me a e-mail?

my web-site: www.independentmassagelondon.co.uk_51335

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDelete